|

Robert

Moray played a major role during the English Civil Wars. He was a Covenanter

General, French Colonel, a spy for Cardinal Richelieu and maybe, a secret

Royalist. He would be accused of instigating the Civil War, betraying his King

and country for money, spying for Cardinal Richelieu, and lying to his French

employers.

But

how much of this is true?

Did

Sir Robert Moray, distinguished Freemason and first president of the Royal

Society betray his King?

In

order to learn more about this very complex man and the exciting times in which

he lived, we will attempt to examine his motives and actions during the war

years. The problem with looking back 400 years is separating

fact from fiction which in Robert Moray’s case is no easy task. Look what

happens when writers feel a need to flesh out details.

His

close friend, John Aubrey wrote only what he believed to be true. Moray went to

university (deduced no doubt because at the time they met, Moray was cultured

and well informed) and then joined the French military under Louis XIII

(absolutely true).[i]

Gilbert Burnet another friend and Royal Society member tells us “he had served

in France . . . He was raised to be a colonel there, and came over for recruits

when the King was with the Scottish army at Newcastle.”[ii]

It is noteworthy that neither

writer provides specific dates, and got some of their facts wrong which is

understandable since their writing style was closer to a gossip columnist than a

historian.

There

are ample contemporary records to prove Moray was given the rank of

Lieutenant-Colonel in the summer of 1642 while still in Scotland, and did not

get promoted to Colonel in the Scots Guards until after the Earl of Irwin’s

death in September, 1645 four years after Newcastle.[iii]

There is no evidence Moray ever

attended any university or college and as we shall see below his own letters

argue against it, but the lack of such evidence has not deterred writers from

creating their own facts.

In

1816 Alexander Chalmers wrote Moray was educated

“. . . partly in the university of St. Andrews and partly in France . .

.”[iv] Now

we have Moray attending college in two countries. His dad would be proud, but

wait, there’s more.

In

1885 Sir Leslie Stephenson adds “Richelieu favored him highly, and he attained

the rank of lieutenant-colonel, probably of the Scots Guard.”[v]

I will come back to the Richelieu story shortly.

Carnegie

Scholar Alexander Robertson is less sure of the facts as he only states; “. .

. he may have served in a French regiment but if so, it would have been the

French Scotts Guards”.[vi]

As

late as 1988, David Stevenson used chance comments in letters written by Moray

to the Earl of Kincardine in 1657 to claim Moray was qualified as an engineer. Moray

mentions in passing that he recalls visiting a mill on a moat 35 years earlier

near Edinburgh, which would have been around 1622. In the second letter, he

recalls being in London 20 years earlier in 1637, in the company of engineers

who pretended great skill in aqueducts. Based on these two scant details

Stevenson claims; “By the time of this latter reference (1637) it would

probably not be inaccurate to call Moray himself an engineer. He had embarked on

a career in French military service, and it appears that he specialized in

technical matters”. Stevenson goes on to base his conclusions not only on the letters

but also on the fact that in 1640 Moray is reported as being appointed by the

covenanters as the Quartermaster General of the Army.[vii]

The problem with this assumption is that these letters indicate Moray was in

Britain and not France during the time he references. It would be unlikely he

could have been there while on active duty in the French army, especially in the

middle of the 30 Years War. Stevensons’ use of a letter sent by Moray to the

Earl of Kincardine where he states he never went to university makes it very

difficult to support his argument that Moray was an engineer.

In

fairness to Stevenson, he makes no such assumption in the introduction of

“Letters of Sir Robert Moray to Earl of Kincardine, 1657-73” in which he

admits he did not know when Moray was made General but suggests once again his

promotion was probably made as a compliment to Cardinal Richelieu.[viii]

In

spite of all these claims there is absolutely no documented evidence that Robert

Moray ever served in France before arriving with his men in March of 1643 by

which time Richelieu was dead. While

his rank of lieutenant-colonel is dated as of June 1642,[ix]

King Charles was still dictating to Lord Lothian the terms under which the

Guards would be allowed to serve in France, as late as January 10th 1643.[x]

So

where did everyone get the idea Moray was in France before 1643? The only

record, if you can call it that, is found in a detailed and very emotional

account by Scottish historian Patrick Gordon who gives the following

unflattering description in his fiery condemnation of both Moray and Richelieu.

“For

how soon the Puritans began to vent their malcontents against King Charles, for

seeking to establish the English form of worship in Scotland by the Service

Book; when the French king daring, his minion by whose advise all was done, and

without whom nothing could be intended nor concluded,-that rich storehouse of

state policy-Cardinal Richelieu, his far-reaching project took hold of this fit

occasion that Britain might also be a sufferer, and no longer a beholder. . .

Wherefore, choosing forth a man fit for his purpose amongst a great many of the

Scots gentry that haunted the French court . . . he chooses . . . Sir Robert Murray, a man endowed with many rare qualities, and a

very able man for the cardinal's project. After he had sounded the depth

of this man's mind, and finding that he was indifferent so

he could make a fortune

whither it were with the king or

the malcontented Puritans, he finds no difficulty to persuade him that his love

to the Scots, by virtue of the ancient league, made him extremely to lament

their case; for that their king was now in hand with was

not, as it was pretended,

merely for religion, but the chief end both of the king and his cabinet counsel

was to reduce Scotland to a

province, without which, he was strongly persuaded that he could never bring the

whole island to one entire monarchy ; but if the Scots, said they will stand to

their ancient freedom, France shall not be wanting in so

just a cause. In end, this

gentleman was so taken in with

diverse favors and courtesies, that the cardinal thrust upon him, as

he takes in hand to return home and work upon this subject; wherein he

advanced so far, as the next

year after he went back to give an account of his endeavors ; and having (as

it was found by event) bound up a secret league between the cardinal

and Argyle, who was then the head of the Covenant. To show how

well the cardinal was pleased, the Earl of Irwin, Argyle's brother, is

chose to have the leading of two thousand men, to be levied in Scotland and send

over to France, with many new privileges, as

that they should be one of the first regiments of the guard, that they

should have their preachers with them, and free use of their religion, with

sundrie other favors; the money is send, the regiment levied, and Sir Robert

Murray made lieutenant colonel.”[xi]

This report is not exactly resounding praise for Robert Moray.

Here he is depicted as a self-serving, soldier of fortune. His character is so

weak he is easily convinced by a promise of money and favors to promote a war

between Scotland and England. Clearly, this is not the same Sir Robert Moray we

have come to know and two questions immediately come to mind.

Who

is Patrick Gordon and why is he saying this about Moray? And, more importantly,

is any of it true?

Patrick

Gordon was a Royalist writing in the last year of his life. The head of his clan

just happened to be George Gordon, the 6th Earl of Huntly, who along

with his uncle James Stewart, Duke

of Lennox re-established the French Scots Guards in 1624. Huntly served as captain and commander of the Scots Guards

from 1624 until his return to Britain in 1637 during which time he claimed to be

badly treated by his French employers. Understandably he was pretty upset by the

generous treatment Irwin and Moray received. [xii]

This hostility between the clans is clearly reflected in Gordon’s report.

This

does not mean that Patrick Gordon did not give some very detailed accounts of

the civil war, he did. However it helps us understand the allegations he makes

against Moray. It is important to remember Gordon is writing in 1649 during the

monarchy’s blackest days. In the last six years he had witnessed its’ utter

destruction. King Charles, the Duke of Hamilton, the Marquis Montrose, and the

head of his own clan, the Earl of Huntly, were all executed between 1649 and

1650.

In

his mind he sees the new freedom and prestige given to the Scots Guards under

Irwin and Moray as prima facie evidence of some great conspiracy at work to

bring down the King with Richelieu and Moray at the center of it. However, his

version of what happened is at odds with the known facts. There is no record in

any biography of Cardinal Richelieu that he ever met Robert Moray. Apparently he

was also unaware that all of the terms concerning the Scots Guards were

negotiated by King Charles himself not in 1639 but four years later. Gordon also

leaves out the fact the troubles with Scotland did not begin with the Book of

Common Prayer but in 1633 when the King attempted to take possession of all

church lands in Scotland.[xiii]

Gordon was a bitter man creating events to meet his own prejudices.

Plainly

there is a lot of bad information floating around but what evidence is there to

give us an accurate picture of the real Robert Moray?

Historian Anthony Wood states that at the time of the signing

of the National Covenant in February of 1638 Robert Moray was General of

Ordinance of the Covenanter Army.[xiv]

We can establish that in 1641 he was still a general at Newcastle. We also know

he was commissioned as a Lieutenant Colonel in the France Scots Guards in the

summer of 1642.[xv] To understand how and why

Moray came to be chosen for that position we need to look at the political

environment of that time.

In 1642, Richelieu’s successor Cardinal Mazarin’s star was

on the rise. He did not share Richelieu’s hatred of the English. In

fact, he had become a friend of Walter Montagu (the brother of the Earl of

Manchester), who was forced to flee England in 1642. Parliament had discovered

that Montagu was raising money for the Royalists as an agent for Queen

Henrietta.[xvi]

Montagu in turn introduced Mazarin to the Queen while she was still in

the Haig which led to a close friendship between the two. In January 1643

Mazarin became France’s prime minister.[xvii]

The

influence of the Queen in the civil war cannot be overemphasized. Charles was

devoted to his petite French wife with whom he had eight children. In 1642 she

had sailed to Holland where she sold her royal jewels to buy shiploads of arms

and men to send back to her husband. Trying to return home a year later she

spent eleven days in one of the worst storms ever to hit the north Atlantic. Her

ships were blown back to Holland leaving everyone on board near death but just

one month later she sailed into the winter storms to bring the needed aid to the

King.

In

June 1644, one month after the birth of her ninth child and with a charge of

treason against her by Parliament, she is forced to flee to Paris.[xviii]During

their separation the Queen writes to Charles almost every day, encouraging him

act like a king.[xix] She was a very determined

lady and if she had been allowed to stay with Charles his fate might have been

very different.

By the mid-1640’s

the idea of a British Republic only

22 miles off their coast was becoming a growing reality and constituted a clear

and present danger to the French Monarchy. It was in their interest to do what they could, short of

declaring another war to support the English King.

Now

let’s take a close look at Moray and see how he fits into this environment.

In every biography of Robert Moray very little is said about his family

other than he was the first son of Sir Mungo Moray. On the surface, it would

appear that Moray had little to recommend him but that is far from the truth.

His grandfather, for whom he was named, was the powerful Baron of Abercairney.

His uncle, Sir David Moray, was Deputy Governor to Prince Henry and one of the

members of the Gentlemen of the Bed Chamber, who controlled access to the King.

Sir David was also one of the better known poets in England and a very

influential force in the King’s court. He was a close friend of Sir William

Alexander, who became Secretary of State in

1629.[xx]

Another of Moray’s uncles Thomas Murray, was the Preceptor and secretary of

Prince Charles.[xxi]

William Murray, Sir Robert Moray’s cousin, had been made the Prince's

whipping-boy. In feudal times a Prince may not be punished by anyone but the

king. A playmate of a lesser rank was punished instead and the bond created

between the two would tend to modify the Princes’ behavior. This rather

symbiotic relationship formed a close bond between the boys that would last a

lifetime. Will became an important member of the Gentlemen of the Bedchamber and

King Charles would reward him

for his loyalty by making him the 1st Earl of Dysart in 1643.[xxii]

Charles Murray was a Groom of the Kings Bedchamber, and Anne Murray,

daughter of Thomas Murray and sister to both Will and Charles Murray, was

governess to King Charles’ Children. King Charles II once told her that he

would do anything for her. In the Civil War she risked her life helping the Duke

of York (later James II) escape to Holland. [xxiii]

King

James set up the department of the Gentlemen of the Bedchamber soon after

arriving in England and restricted it by law to no more than 18 members. Of

these, 12 members were related in one way or another to Robert Moray.

1.

William

Murray, Robert

Moray’s cousin.

2.

Patrick

Murray another Cousin.

3.

David

Murray, Robert Moray’s uncle.

4.

Sir

Robert Douglas. He married into the Moray family in 1610.

5.

Lord

Holland, Henry Rich who would work with Moray for a peace in 1645-46.

6.

James

Hamilton, cousin to the King and closest advisor.

7.

William

Alexander, Secretary of State and close friend of Thomas Murray.

8.

Sir

James Young (his father was a close friend of Thomas Murray).

9.

Mungo

Moray, (not

Robert Moray’s father as he was still active in 1648).

10.

Sir

David Cunningham of Robertland. (The author of a letter in 1628 describing a

“secret fraternity” within the Bedchamber swearing undying loyalty to the

King. See note 43)

11.

Sir

Digby of Ireland, who also served the royal family by trying to raise an army in

Ireland.

12.

Sir

Kenelm Digby, could be seen as having a bias towards Moray by virtue of his

close relationship to his brother. [xxiv]

Few

Scots had more political influence in both England and Scotland in the

mid-1640’s than Robert Moray. That kind of clout certainly seems to answer why

someone might want to enlist his aid in gaining favor with the King. We will

examine the when and where he was recruited to go to France shortly but before

we discuss those details let’s review a few of the major events of King

Charles I early years.

Charles

had alienated most of his subjects even before becoming King by allowing himself

to be dominated by the Duke of Buckingham, who managed to offend every country

in Western Europe. As King, Charles was consistent. He invariably made the wrong

decision. His wife constantly chided him to act like a King but it was beyond

him to do so. His inability to make important decisions coupled with his

stubbornness on religious issues would continue to spark unrest throughout his

reign. In the end it would cost him his life.

His

problems with parliament began immediately after his coronation. Charles wanted

to obtain funds from parliament to go to war against Spain but the House of

Commons refused to comply. They argued the King had already lent ships to King

Luis XIII of France, who used them to fight the Protestants in Rochelle, not a

popular move for a Protestant monarch. Incensed by their defiance the King dissolved parliament.

Next, he appointed his main opponents to the office of Sheriff in their home

counties thus prohibiting them from serving in parliament. Unfortunately for

Charles this backfired and the members of parliament were even more hostile to

the king.

On the 2nd of March 1629, the King dissolved parliament again and

imprisoned nine members, leaders of the opposition. With the aid of Bishop Laud

and the Earl of Stafford he would rule England without a parliament for nine

years.

In

1633 Charles went north to be crowned King of Scotland and immediately attempted

to grab all the church lands in Scotland by pushing through an act giving

himself total control of the Church. The Scots voted down the act, whereupon the

King had the clerk recount the votes and declared the act had passed.

In

1634 when a copy of a pamphlet criticizing the King’s actions, were discovered

in the possession of John Elphinstone, Lord Balmerino, the King put him on trial

for sedition. For the Scots this was a clear sign King Charles no longer

considered himself a Scot.[xxv] They needed only a spark

to ignite them into open revolt.

King Charles provided the spark in 1637 when he attempted to force his

Book of Common Prayer on the Scots, in which the churches were to be set up very

similar to the Roman Catholic churches. In February of 1638 the Scots drew up

their national covenant, binding those who signed it to defend their religion to

the death. Anthony Wood states that

Moray was a general of the covenanter army from the beginning of the movement.[xxvi]

One

year after the Scots signed their covenant Lord Stafford marched north at the

head of a small, ill-trained force of English troops expecting to quell the

Scots. Many of his conscripts were armed only with bows and arrows. Shorty

after he crossed the border he came face to face with a 30,000 man Scottish army

armed with muskets and artillery pieces and led by the greatest Scottish general

of his time, Alexander Leslie.[xxvii]

Stafford

had brought a knife to a gun fight.

Faced

with certain defeat Charles was forced to sign the treaty of Berwick on the 18th

of June. However, both sides knew the King had no intention of living up to its

terms. Without a parliament to vote

him funds Charles could not afford to keep his army intact and allowed it to

disperse, while the Scots kept their army in place. It was only a matter of time

before the next armed conflict.

If

we are to believe Anthony Wood[xxviii]

there were at least two generals serving under Alexander Leslie at this time.

One of them was Alexander “Dear Sandy” Hamilton, an artillery genius who had

designed the highly portable “Dear Sandy Stoups” cannon which would see

action one year later. The other was Robert Moray. This

raises an important issue. Leslie was an experienced combat veteran. He would

choose his generals from men he had served with, trusted their judgment, and who

he knew would not panic under fire. If Moray was one of his generals it is

highly probable he served under Leslie in Germany during the 30-Years War. This

would explain why a third former Leslie

general, the Marquis of Hamilton, would travel to Newcastle and cross the battle

lines between the English and Scots forces not once but twice to serve as Deacon

first at Sandy Hamilton’s, and then one year later at Robert Moray’s,

initiation into Freemasonry.

In August 1640 it was the Scots who moved first. They crossed the Tweed

and advanced on Newcastle. It was a fight neither side seemed anxious to start.

During the morning the English and Scots stared at each other across the river

at Newburn, a few miles west of Newcastle. Hostilities finally broke out when an

English musketeer shot a Scottish officer relieving himself at the river bank.

What

happened next was more of a rout than a battle. Sandy Hamilton, had placed his

sixty pieces of light artillery on the high ground and began to shell the

English lines. A cavalry charge was quickly disbursed by the accuracy of a

battery of nine cannons ending the English resistance. They deserted their posts

and beat a hasty retreat. Although less than 60 English troops had been killed

in the first skirmish the English commander decided the battle could not be won

and abandoned the heavily fortified Newcastle. To their amazement, the Scots

took the castle without having to fire a shot.[xxix]

Once

again Charles was compelled to sign a treaty with the Scots. This time he agreed

to pay them £850 a day for the maintenance of their army to prevent any further

incursion into England. Since he

did not have the money he was forced to convene parliament. This gave them an

opportunity to remove the King’s strongest ally. They blamed the

₤1,000,000 cost of the war on Lord Stafford and demanded he stand trial

for treason.

Parliament

did agree to pay the Scots Army ₤220,000 in what they termed “Brotherly

Assistance”. However, promising and actually paying that amount were two

different things. [xxx]

In March 1641 Robert Moray writes a letter from Newcastle to Lord

Carnegie about the trial of Lord Stafford in London indicating he may have been

in London during the trial.[xxxi]

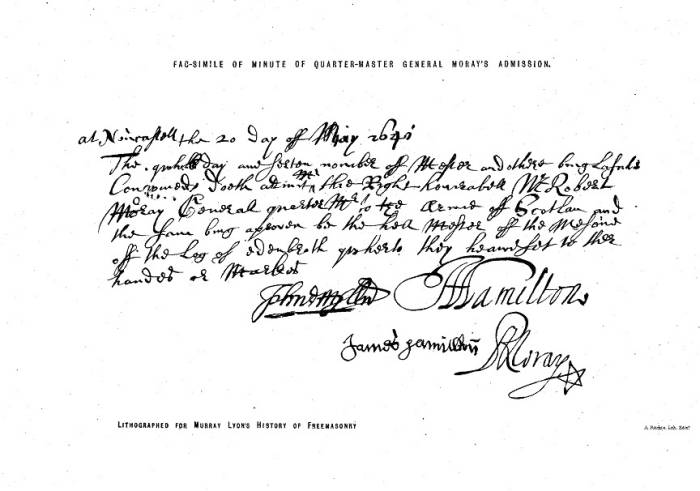

On

the 20th of May the minutes of the Lodge of Edinburgh at Newcastle,

record the admission of Mr. and Right Honorable Robert Moray, General

Quartermaster to the Army of Scotland. The two Deacons at the initiation were

named Hamilton. One was James the Duke of Hamilton, Gentleman of the Bedchamber

and King Charles’ closest advisor. The other was Alexander “Sandy”

Hamilton the Covenanter General of Artillery who routed the English at

Newcastle, both of whom had served as generals under Leslie in Germany ten years

before. [xxxii]

At

about this time Cardinal Richelieu was informed by Jean du Montereul, who was

his Charge d’Affairs in London, the war was over and the armies of both

kingdoms would soon be dispersed. He promised the Cardinal there would be plenty

of soldiers available to serve in the French army.[xxxiii]

In

October the French Ambassador visited Lord Argyle seeking help in recruiting

soldiers for the French Scots Guards. They agreed that Argyle’s Brother would

be given command of the guards, with a salary of 375 Scots Pounds per month.

However, the King’s approval was needed and Argyle was not on good terms with

him, so he proposed Moray, a close friend of the court as the number two man to

make the deal more appealing to the king. [xxxiv]

The

plan worked.

In

June 1642 Moray is notified of his rank as lieutenant-colonel but it is March of

1643 before Moray and the Earl of Irwin would arrive in France with their men.

Charles delayed the deployment while he negotiated with the French. On

January 10th, the same day he knighted Robert Moray the King was

still dictating terms, including religious privileges for the Scots Guards. [xxxv]

One

side note to all this is that by the time Moray actually reached France,

Richelieu had been dead four months which really blows holes in the conspiracy

theory described by Patrick Gordon.

Immediately

upon arriving in France, Moray and the Scots Guards are deployed and enjoy a

series of victories during the summer and fall. But their luck runs out as

winter approaches. In November the French Army suffers a crushing defeat at

Tuttlingen in western Germany. Four thousand men were killed or injured and

7,000 captured including Robert Moray.[xxxvi]

He was taken to Bavaria where he should have faded into history but Fate had

other plans.

In England the tide of war had turned against the Royalists.

By June 1644, the loss at Marston

Moor to the combined forces of Scots and English Parliamentarians

under Leslie and Manchester reduced Royalist control to less than 25% of the

Island. They were now barely holding on in the Southwest and Wales. With each

victory the attitude of the English towards the Scots was becoming more and more

hostile. It was obvious to the Scots the promises made to them by the English

parliament just a few months ago would not be kept. In order to avoid a

political disaster the Scots needed to save the very crown they had been

fighting to get rid of.

In

October of 1644 the Scottish government sends Sir Thomas Dishington to Paris to

suggest to Cardinal Mazarin if the release of Sir Robert Moray could be arranged

he might be of great use to both the French and Scottish causes.[xxxvii]

While France had no agreement in place regarding the exchange of prisoners, a

ransom was arranged for the release of Moray from Germany. The man chosen to

arrange the ransom was Robert Murray of Priestfield the Brother-in-Law to

Dishington, and another of Moray’s relatives.[xxxviii]

In fact, when King Charles II knighted Murray in 1661 and made him Lord Provost

of the city of Edinburgh, the mortgage on his land was held by none other than

Sir Robert Moray.[xxxix]

Regardless

of how the ransom was funneled, the money came from the Scottish government, and

was later made a public debt.[xl]

By the 28th of April

1645 Moray was free and on his way to London.[xli]

On June 14th the roundheads defeat the royalists at Naseby.

King Charles and the last remaining English royalists are surrounded at Oxford,

his life spared only by the reluctance of Sir Edward Montagu, Earl of

Manchester, who wanted a negotiated peace to attack his King. His second in

command Oliver Cromwell, would later bring charges against the General and force

him to retire.

It

is at this critical point that Cardinal Mazarin sent Jean du Montereul to Moray

in London to attempt a diplomatic solution to the war. Moray is still being paid

by France as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Scots Guards and now is an agent of

both France and Scotland.

In the third week of September, Montereul notified Cardinal Mazarin that

he had a proposal of peace from the Scottish Commissioners but thought it would

be best to seek Henrietta’s help. Since the Earl of Irwin, Commander of the

Scottish Guards, had just died, Montereul recommends promoting Moray so he would

have a reason for traveling to France without raising suspicions.

He states “that it may please your Eminence to give the command of this

regiment to Sir Robert Moray, whom I have already mentioned in this letter, and

of whom they have spoken in the highest possible terms, and who is really a very

estimable person. . . Sir Robert Moray is in our service; he is very intelligent,

and has powerful friends in Scotland and in England.” [xlii]

Montereul neglects to inform Cardinal Mazarin the real reason Sir Robert

Moray must travel to France. The Scottish Commissioners demand the King must

sign the covenant, something Montereul is sure the King will never agree to. His

hope is that Moray and Will Murray can influence the Queen to convince Charles

to sign.

The reason for Will Murray being in France at this time is due to some

difficulty with the Marquis of Montrose (and perhaps a request by the Queen). In

1641 Charles and Montrose had planned to arrest Argyle for treason and put

Montrose in his place but Argyle learned of the plot and arrested Montrose

before he could move against him. When Charles came north to Edinburgh later

that year Will Murray was caught in the castle with a key to Montrose’s cell. Later

Montrose became convinced that Will Murray never intended to free him and was

the one who betrayed him to Argyle. Conditioned by a lifetime of being punished

for Charles’ mistakes Will Murray took the blame and was shipped off to France

in 1644 with the Queen.[xliii]

Montereul,

writes to the Cardinal about Moray; “I have again assured them (the Scottish

Commissioners)” he writes “you would listen to Sir Robert Moray, and that it

was only necessary to think of improving the proposals they wished to make to

the King of Great Britain in such a manner as to enable him to accept them with

honor.”[xliv]

Although

Moray tried for a month to convince the Queen he left France thinking he had

failed. Unknown to him she had agreed to help but only on the condition the

Cardinal not tell Moray for fear her negotiations with the Pope would be

jeopardized.

In

the meantime word had spread that Charles has already indicated to the

Independents in parliament that he was willing to negotiate a settlement with

them.[xlv]

The terms of their offer are so

generous it is hard to imagine why the King did not agree immediately to them.

Had he done so, the war would have been over. He would only have to agree to

ultimately allow them to retreat to Ireland to enjoy the liberty of worship. In

return, they were ready to immediately turn over to the King, the New Model army

along with the fortresses in its possession.[xlvi]

He would never get as good terms from the Independents again. However, the King

viewed the terms as an abandonment of the Irish Catholics and would not agree.

In mid-December the President of the Scottish Commissioners in London,

Lord Balmerino, was so frustrated by the Queen-Regent’s refusal to send Will

Murray back to the King, where he could be of use to the Scottish cause, he

threatened to call off all negotiations. It took Moray to calm him down and

agree to stay in London.[xlvii]

By

now it was decided that a direct appeal to the King was needed and Montereul

would go to Oxford and try to convince the King to come to terms with the Scots.

As he prepares to for the visit he is in close negotiations with representatives

from both England and Scotland. The English are represented by the Earl of

Holland, Henry Rich, one the Gentlemen of the King’s Bedchamber and an English

Presbyterian. He is worried about having the King come to London. He believes it to be too dangerous since the Independents are

ready to intercept him. He and his

friends in England would rather have the King go to the Scots. Sir Robert Moray,

Baron Balmerino, and the Earl of Lauderdale, John Maitland, represent Scotland.

After

the meeting Montereul writes that Moray assured him Baron Balmerino would write

a letter to Lord Loudoun in Edinburgh to convince the Scottish parliament to

accept whatever proposal they could get out of the King,[xlviii]

but there is no other evidence that Moray made such a promise. The Earl of

Holland, Montereul and Moray stay together planning strategy late

the night before Montereul leaves for Oxford to visit the King, indicating a

real concern for the survival of the monarchy that crosses all three national

boundaries. [xlix]

We have two conflicting reports of what went on in Oxford, one from

Montereul and one contained in a letter from the King to the Queen-Regent.

Montereul reports correctly that the King is adamant about not signing the

covenant but claims to run into a brick wall when he pleads for Will Murray’s

return. He says the King is heartbroken about Montrose who was recently defeated

by Sir David Leslie in the battle of Philiphaugh,[l]

and requires Murray go to Montrose and get his permission before he can return

to court.[li] This would have been

impossible since Montrose was hiding in the highlands and is probably more of an

indication that Charles did not trust Montereul as evidenced in the wording of a

letter the King writes the very next day to the Queen. It is apparent that the

Queen had already told the King the details of the Scottish proposal that Moray

had taken with him to Paris in October.

Oxford, Thursday, Jan. 8, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

I

find by Montrevil that his chief errand here is to try if he can obtain more

from me than Sr Robert Murrey could from thee, for he rigidly insists upon my

consent for the settling of the Presbyterian government here (indeed he sayth it

will be but temporary, which likewise he can shew me no probability), alledging

that less will not be accepted.

CHARLES

REX.

. . .and for Will. Murray's coming over I like that well too, so that I may have

a pass to send him or somebody else to Montrose, whereby he and I may know the

state of one another's condition ; and this I believe may be easily obtained, to

procure Will Murray to be a negotiator in the Scotch treaty.[lii]

This year was destined to be a bad one for the King and all who worked to

try to save the monarchy. In January letters from the Queen-Regent fell into the

hands of the English Parliament which disclosed that the King was negotiating

with the Scottish Commissioners.[liii] A few weeks later Will

Murray was arrested at Canterbury and would not be released for seven months. In

the meantime, while the King was negotiating with everyone he was also planning

his escape to France.

Oxford,

Feb. 1st, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

“

. . . As at no time I desire to conceal anything from thee, so at this it is

most necessary to shew the truth of my present condition, which is that,

considering my own weakness, the small or rather no hopes of supplies from

either Ireland or Scotland, and the rebells' strength, I am absolutely lost if

some brisk action do not recover me, wherefore, having thought of many, I have

at last resolved on this. I shall, by the grace of God, without fail, draw into

a body by the end of this February 2,000 horse and dragoons; with these I

resolve to march into Kent, where I am confident to possess some important place

not far from the sea-side (not being out of hope of Rochester), where, if I have

either time or sufficient strength to settle myself, I shall esteem myself in a

very good condition; wherefore I desire thee, as thou lovest me, to hasten those

men which Jermyn promised me by the middle of March ; they must land at or near

to Hastings, in Sussex. . . Besides, thou must know that, whether they come or

not, I must venture upon this design: now my danger is least the rebells should

so press upon me as not to give me time to make myself ready, which they will

not be able to do if the 5,000 men come over as I have said, but if not, then it

will be likely that I shall be so prest as not to stay long in this kingdom, and

then all is lost.”[liv]

C R

Unfortunately for Charles, the Queen who had always stood by his side,

devoting her life to his cause, and who had gone so far as to send Lord Kenelm

Digby to negotiate with the Pope on behalf of the King,[lv]

now realized his cause was lost.

Charles writes to her on February 19th begging again for

5,000 soldiers to help him break out of Oxford. She responds the next week but

not with the news of the rescue attempt he had hoped for but with a different

kind of solution. She writes: “My advice is to make peace at any price”.[lvi]

In the meantime the war had taken another turn for the worst.

MONTEREUL

to CARDINAL MAZARIN. London Feb 1st, 1646.

.

. . “News reached here this morning of the taking of Dartmouth by storm, this

is the last seaport the Royalists possessed. Sir Robert Moray and I wrote to the

Chancellor of Scotland, on Tuesday last, to ask him to solicit in our names from

Parliament the permission to raise twelve hundred men for the service of his

Majesty. Sir Robert thinks it may be possible to ship three or four hundred in

passing at Newcastle.”

It

is important to look closely Sir Robert Moray’s reaction to the news of the

loss of Dartmouth. Note the wording he uses. He does not want men to capture or

to safeguard the King to Scotland. He uses the words “for the service of his

Majesty”. For him to want to raise 1,200 men in Scotland to fight for the King

is contrary to the Scot’s interest. The Scots, who are presently allies with

the English, would rather force a weakened monarch to seek safety in Scotland.

Helping the King survive on his own would not suit their purposes at all. Nor is

it consistent with the French position, who also desired a weak King in the

hands of the Scottish Army. In fact, the only people to whom this position would

be consistent with would have been a small secret fraternity of Scots Royalists,

who in 1628 formed a pact in which they state they were, “taking in sundrie of

the Bedchamber and others of quality and worth, and have forever hereafter

excluded and discharged to admit of any but his majesties servants”.[lvii]

At

least two-thirds of the Gentlemen of the Bedchamber in 1628 were related to

Moray.

Although

Moray was working on behalf of both France and Scotland, one thing is certain;

his actions that day were those of a Royalist.

As if King Charles did not have enough problems, by the end of the month

news of his negotiations with the Independents had leaked out and on March 1st

Montereul reports the news to Cardinal Mazarin.[lviii]

He is now desperate to reach a settlement France could support.

After the capture of the Queens’ letters in January exposing that

talks between the King and the Scots were underway no one wanted their signature

on any document. Montereul turned again to Moray who agreed to risk his life by

signing his name to a proposal to the King on behalf of the Scottish Commission.

The agreement states in part:

“ . . . it may please said Majesty . . . to write two

letters, one to the English Parliament and the Scottish Commissioners in London,

and the other to the Committees of the Scottish Parliament, by which he gives

his consent to the three propositions regarding religion, the militia, and

Ireland which were formerly drawn up at Uxbridge, and to the demands of the City

of London, which are of little importance, with promise to ratify them by acts

of his Parliaments, and to do all that may contribute to the establishment of

affairs, ecclesiastical and civil, by the advice of his Parliaments, and that

his said Majesty . . . sign the covenant either before going to the army or on

arriving there, as he chooses.”[lix]

Montereul is certain that the King

will never sign the covenant and pleads with Moray to find a way around it.

Moray finally agrees that in lieu of signing the covenant itself, the Scots

would be satisfied if the King would approve it in a letter to be sent to both

parliaments. Montereul writes later about Moray “who acted in this negotiation

with the greatest possible tact and Prudence and with a care that cannot be

expressed”[lx]

However, once he has Sir

Robert Moray’s signature, Montereul makes

an abrupt about face and decides, since it is not expressly mentioned, the King

no longer needs to sign nor approve the covenant. This was a grave error for the

Scots’ intent was merely to allow the King to save face by approving the

covenant in his letter.[lxi] This issue will be the

wedge that for a while at least, ruins the friendship between Montereul and

Moray after the Frenchman arrives in Newark.

In March 1646 Montereul is

finally given a passport from the English parliament to travel to Oxford to take

leave of the King on his way out of the country but is expressly forbidden to

return to London. He arrives in Oxford on March

17th but if he expected

the King’s deteriorating situation to make him more amenable to an agreement

he was mistaken. Charles’ letter to the Queen dated March 22nd

indicates his reaction to the latest offer by Montereul.

Oxford,

March 22nd, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

Ill

success, mean spirits, and Montrevil's juggling, have so vexed

me, . . . As for Montievil's negotiation, I know not what to say to thee,

because he would have me believe his word before thy letters, which indeed I

cannot do, and he makes such interpretations as pass my understanding. For

example, he would persuade me that you will be content that the peace of Ireland

should be sacrificed to please the Scots ; and that to suffer my friends to be

banished . . . is not forsaking them;and in particular Mountrose must run this

fortune, or else no agreement with the Scots, but this I will constantly refuse

. . .

CHARLES R

The

next day the King writes to the Scottish Commissioners in London demanding

better terms including an agreement with Montrose. The King states that he would

give full contentment, if he could be persuaded that this would not be against

his conscience. Four days later Montereul,

demands a speedy answer but the original letter was not received by Sir

Robert Moray until April 2nd, by which time the Frenchman had taken

things into his own hand. He promises Charles without any authority to do so,

that the King and Queen of France would be his

surety that he would be received in Newark “In all the Freedom of his

conscience and honor.”[lxii]

In the meantime the King is losing patience with Montereul as evidenced

by the last paragraph in his letter to the Queen Regent on March 30th.

Oxford,

March 30th, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

.

. . Concerning which treaty, I have commanded secretary Nicholas to give thee a

particular account, yet must tell thee, that if Montrevil had not trifled I had

been in the Scotch army long before now, without sending my last message ; but

the sending of it made him open his pack, which he did for fear of my going to

London, least I should there join with the Independents against the Scots.[lxiii]

By

now the strain on the King is showing. There will be no rescue for him and his

options are rapidly dwindling. He trusts no one and will change his allegiance

back and forth over the next eight months as he searches for a way out.

On

April 2nd, unaware of Montereul’s false assurances to the King, the

Scottish Commissioners allow Moray to agree to the terms of the Kings request.

The King now thinks he is in a far better bargaining position than he is in

reality. However, he is about to get a rude awakening.

At

this point, as Montereul prepares to leave for Newark, all of the parties are

lying to each other and each had to be aware they in turn were being lied to.

The basic situation had not changed in over five months. The King had no

intention of signing the covenant but tried to get the Scots to believe that he

‘might be persuaded’ while at the same time planning an escape to France.

Montereul needed the King to go to the Scots instead of to Parliament in order

for France to have any influence on events and put a stop to Cromwell from

creating a British republic. He

lied to the King about having an assurance from Louis XIII because he was afraid

the King would go to London without it. In the meantime, Moray and the Scots had

never waivered in their demand that the King must sign the covenant and had to

be aware that he would never give in to their demands.

The

only obvious reason for Moray to agree to the King’s terms had to be motivated

by a very real fear that the King might turn to the Independents and travel to

London instead of North to Scotland. If that happened the Scots would have lost

the only bargaining piece they had to get any concessions from the English

including being paid the 300,000 pounds owed them in back pay for their army.

Of

all the parties involved, only the Frenchman believed his own propaganda and was

furious when he was not received with open arms when he reached the Scottish

Army.

He

writes two letters to both Secretary Nicholas and the King. His first letter,

warning Secretary Nichols not to

allow the King to move north, is returned when his messenger cannot get through

the lines. His second to Nicholas dated April 16th states that

although things had looked bleak for the King he now believes he has an

agreement whereby the King can come to terms with the Scots[lxiv].

The agreement lasts less than one

week as evidenced by reaction by the King’s words in his letters to the Queen

Regent on the 21st and 22nd .

Oxford,

April 21st, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

.

. . In short, the Scots are abominable relapsed rogues, for Montrevil himself is

ashamed of them, they having retracted almost everything which they made him

promise me, as absolutely refusing protection to any of my friends longer than

until the London rebells shall demand them, . . In a word, Montrevil now

dissuades me as much as he did before persuade my coming to the Scotch army,

confessing my knowledge of that nation to be much better than his.[lxv]

Oxford, April 22nd, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

.

. . their base, unworthy dealing, in retracting of allmost all which was

promised Montrevil from London, even to the being ashamed of my company,

desiring me to pretend that my coming to them was only in my way to Scotland.

But the pointing at their falshood must not make me forget to give Montrevil his

due, who seriously hath carried himself in this business with perfect integrity.[lxvi]

Moray

and the Scottish Commissioners in London were not involved in the King’s final

decision making process due to Moray suffering a badly sprained ankle which

leaves him incapacitated until late May.[lxvii]

The

King alone and desperate finally decides he must leave the dwindling safety of

the town but instead of heading north he heads southeast to London. Along the

way he worries that he will not be received well by the Independents and changes

his mind. He turns north for Norfolk where, if he gets no assurances from the

Scots by then, he intends to leave England for France. The Scots have no

intention of moderating their demand but the King who had deceived everyone for

years now deceives himself. He chooses to believe a letter sent by Montereul

from his lodging at Southwell, stating the Scots will not press him to do

anything contrary to his conscience.[lxviii]

With

nowhere left to go the King heads north for the Scots and a polite but confined

existence at Newcastle.

Throughout

the summer and early fall the King uses the Duke of Hamilton and his Brother

along with Sir Robert Moray to try one last attempt at reaching an agreement

with the English parliament. It is a doomed effort, Cromwell now has a choke

hold on parliament.

On

September 7th, Will Murray is released by the English and allowed to

travel north to join the King. However as seen from the following extracts of

letters sent to the Queen Regent it takes a few weeks for the King to trust

Murray once again.

New

Castle, Sept. 7th, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

I

am freshly and fiercely assaulted from Scotland for yielding to the London

propositions, likewise Will. Murray is let loose upon me from London for the

same purpose . . .[lxix]

New-Castle,

Sep. 14th, 1646.

DEAR

HEART

.

. . He [Will. Murray] hath been so far from pressing me to a total compliance

(as I did expect), that he protests against breaking the Irish peace and

abandoning my friends. He presses even those too many points of religion and the

militia more moderately than any have yet done, for he confesses that I must not

sign or establish the covenant . . .[lxx]

New-Castle,

Sept. 21st. 1646

DEAR

HEART

.

. . Will. Murray and I have not yet concluded upon our private treaty, but by

the next the queen shall hear a particular account of it.[lxxi]

On

September 26th the King after conferring with Sir Robert Moray writes

to Hamilton assuring him the King is aware of his loyalty. A similar

letter is sent to Hamilton from the Queen which leads one to believe that both

feel Hamilton is the key to healing relations between the King and parliament. [lxxii]

By the early part of October Will Murray is an accepted member of the

team once more.

New-Castle,

Oct. 12th, 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

Not

having been able before this day to make Will. Murray's dispatch, I cannot,

until the next post, send thee my answer to the propositions. Will, seems to me

to be very right set concerning all my friends in general. . .[lxxiii]

New-Castle,

Oct. 24th. 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

.

. . Their intentions to assist me are easily seen, but most of all (in my

judgment) by their rigid sticking to the covenant, which Sr Rob. Murray told me

(not above five days ago) was ever meant in his treaty with thee; and all the

reason he gives me why it was not mentioned is because it was thought needless,

as being necessarily understood, so that it will be easily seen that my

conscience is neither the only nor chief impediment of their joining with me.[lxxiv]

The King writes a constant stream of letters to Hamilton and his brother

as they serve as his intermediaries with parliament in a last minute futile

attempt to find a solution to his situation.[lxxv]

Moray is also keeping up a steady correspondence with the Duke of Hamilton.

However, while he appears to have the Duke’s trust there seems to be some

disagreement between Moray and the Duke of Lanerick, Hamilton’s hot blooded

brother who wants the king to take action.

Sir

Robert Moray To The Duke Of Hamilton.

1616,

Oct. 17.

.MAY

IT PLEASE YOUR GRACE,

What

your brother writes I need not touch, .

. . I have spent all my gall upon your

brother for his stay, notwithstanding your excusing him."

In

the margin is a note probably written by the Duke’s Brother William, Earl of

Lanerick, which states:

"Yet trust me not so much as I deserve. L.''[lxxvi]

By

early December every scheme Charles had come up with to escape his predicament

had fallen apart and he was at last willing to consider any attempt to escape.[lxxvii]

In the following letter we can deduce that Moray, Will, and the duke had devised

a bold but very dangerous plan to rescue the King from his confinement in the

castle.

New-Castle,

December 12th 1646.

DEAR

HEART,

.

. . I am not found altered in my conscience, and that I will not authorize the

covenant, without which (I tell the very words) all that can be offered will not

satisfy: yet, for their personal duty, I have much assurance from duke Hamilton

and earl of Lanerick. If they make good what is promised in their name (and I

will put them to it), my game will be far from desperate, but, having little

belief that these men will do as they say, I will not trouble thee with

particulars, until I give thee some more evidence than words of their realities.[lxxviii]

In

a letter to the Duke of Hamilton dated the same day, Moray advises the Duke the

King is aware the English have approved a payment of 200,000 pounds to the Scots

for his return to England. Everyone is aware that time is fast running out. [lxxix]

On

December 17th Lanerick writes to the King begging him to take action

immediately.

“That

whatever your majesty intend to do be quickly done, for our resolutions here

will be sudden and sharp. Whatsoever other men’s carriage be, I am resolved to

die rather than concur with them.”

There

is no mention of a specific plan to help the King escape in any of the letters

between Moray and Hamilton, and although

there are secondary reports of the attempt by Moray and his cousin Will to free

the King[lxxx],

the most detailed is found in Burnet’s “Lives of the Hamiltons” on

page 391.

The

plan is set for execution on Christmas Eve when the garrison will be getting

ready to celebrate the birth of Christ and their vigilance at its lowest. By

happenstance it was also the day when the English parliament voted to have the

King moved back to England.

“The

Design” says Burnet, “was thus laid: Mr. Murray had provided a vessel at

Timmouth, and Sir Robert Moray was to have conveyed the King thither in a

disguise; and it proceeded so far that the King put himself in the disguise and

went down the back stairs with Sir R. Moray. But his majesty, apprehending it

was scarce possible to pass through all the guards without being discovered, and

judging it hugely indecent to be caught in such a condition, changed his

resolution and went back; as Sir Robert Moray informed the writer. This came to

be known to some: and one suspecting the duke was in on it, wrote to him

earnestly to concur in no such design.”[lxxxi]

After

the attempt failed, word leaked out and an order was sent out from London for

Moray and Will Murray’s arrest.[lxxxii]

Apparently no one wanted to bring the issue to trial and Moray and his cousin

remained at large.

By

February 1647, Will Moray is back with the King[lxxxiii]

and Montereul seems to have come to terms over his past differences with Moray.[lxxxiv]

Moray

is now dealing with the consequences of his actions. He had misled the King in

coming to Newcastle, hoping that the King would see the political necessity of

signing the covenant but he had failed to recognize how deep the King’s

aversion to it ran. Moray now sought support for military action to rescue the

King from the English Army.[lxxxv]

During

the early part of the year it looked like the Marquis of Argyle would raise an

army of Presbyterians to take on the English Independents and Moray supported

the move to bring Prince Charles to Scotland. Hamilton, who had fallen out with

Argyle, would not join with him and did not support the Engager movement until

late summer. That was when church opposition to military intervention caused

Argyle to have second thoughts.

Moray

now enthusiastically joined with Hamilton because they would offer more lenient

terms with the King. After gaining the King’s approval James Stewart, Lord

Traquair, left for France to talk to Prince Charles about joining Hamilton in

the rescue effort.

By

May 1648 the Engagement policy had support throughout Scotland and Sir Robert

Moray sailed to France to take care of some business with his regiment and to

pursue the plan to get the Prince to come to Scotland.[lxxxvi]

On

August 10th Lauderdale traveled

to meet the Prince and six days later

persuaded him to join the Duke's army. Moray

was commanded by the Prince to travel to Holland to raise funds and arms but

before he could leave France word came of Hamilton’s defeat and capture at

Preston.[lxxxvii]

The second Civil War was over.

Charles

would squander one last opportunity to escape his destiny with the axe. In

October, after Hamilton lost the battle of Preston, the King was kept under a

loose guard at Hampton Court. Towards the end of the month he finally made good

his escape with Sir John Berkley and John Ashburnham and by nightfall reached

the coast between Southampton and Portsmouth across from the Isle of Wight.

There

appears to be some disagreement as what to do next. Sir John wanted the King to

make good his escape to the continent but instead the King made the worst

decision of his life. He sent Ashburnham and Berkley to seek help from Colonel

Hammond, Governor of the Isle of Wight. Hammond duped Ashburnham with promises

he never meant to keep and convinced him to take Hammond, the commander of the

castle, and some soldiers back to the King. When Ashburnham walked into the

Kings Bedchamber to advise him that Hammond was downstairs, the King was so

furious that he reduced Ashburnham to tears. The

next morning Hammond took the King into custody and five months later he was

beheaded by Cromwell.[lxxxviii]

So

now we come to the final question left unanswered did Sir Robert Moray betray

his King?

In

answering that question we need to consider not only the events prior to January

of 1649 but also Moray’s dedication to King Charles II during the 1650’s.

Here

is what Alexander Robertson, author of ‘The Life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier,

Statesman, and Man of Science” wrote: “During the young King’s exile,

Moray devoted himself to his cause in Scotland after the Restoration. He was an

honored friend (of the King). It is impossible to doubt his faithfulness to the

son, and therefore it is difficult to discredit his loyalty to the father.”[lxxxix]

Conclusions:

John

Aubrey’s comments about Moray serving under Luis XIII are accurate. Aubrey

gives no dates of this service but it has to be after his appointment in July

1642 as a Lieutenant Colonel in the French Scotts Guards.

Aubrey, Burnet, Anthony Wood, Alexander Chalmers, Leslie

Stephenson and strangely enough David Stevenson got it wrong about Moray’s

education. Moray states that he never attended university.

Patrick Gordons’ account of Moray’s conspiring with Richelieu is

totally unsubstantiated as is his other conspiracy theory involving the Swedish

Chancellor which follows this passage in his book. The fact that all of the

previous writers, with the exception of Alexander Robertson, used this slander

as a basis for constructing a relationship between Richelieu and Moray is

unfortunate. There is no evidence that the two men ever met.

There

are no records of Moray’s military service prior to his being named as a

General for the Scots army in 1638-39. However,

I believe all of the Moray biographers made a huge mistake by failing to

question why the most successful Scots general of his time made Moray a general

of the Scots army in time of war? It is not reasonable to assume a combat

veteran with Leslie’s experience would include any but his most trusted

officers on his general staff. Nor did any of these writers question the fact

that both of the Deacons at Moray’s initiation also served as under Leslie in

Germany in the 1620-1630’s.

A

young Scots officer serving under Leslie in Germany could have counted on

attaining the rank of colonel. In fact, we know that Alexander Hamilton, Munro,

and several others did just that. If Moray served under Leslie from the time he

was 18 (1628) until the peace of Prague in 1635, when many Scots returned home,

he had ample time to be promoted to colonel.

It

is logical for Leslie to choose his General Staff from such a cadre of veteran

colonels. This makes far more sense

than the belief espoused by all of the writers that Moray was promoted to

general after serving in France as a Scots Guard. One must remember that Huntly

as commander of the Scots Guards from

1624 until 1637 only attained the rank of Captain after more than 12 years of

service and returned home a bitter, disillusioned, man.

If Moray served under Huntly he would have remained a lieutenant and

being raised from lieutenant to general in one step is just not credible.

Research

is an unending task but for now, I think the circumstantial evidence points to

Moray moving up through the officer ranks under Leslie in Germany rather than

stagnating in France under Huntly.

Notes

[i]

Brief Lives, John Aubrey Page 81

[ii]

Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Times, by Gilbert Burnet; Martin

Joseph Routh; Thomas Burnet, et al;Clarendon Press Oxford 1823 Page 101

[iii]

The Diplomatic correspondence of Jean du Montereul: Translated by J.G.

Fotheringham Scottish History Society 1898 Pages 91, 113

[iv]

The General biographical dictionary by Alexander Chalmers. Printed

for J. Nichols London, , 1812-(1816) Pags 341-342

[v]

Dictionary of National Biography by Sir Leslie Stephenson,

Published Oxford University 1885 Page 400

[vi]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 2

[vii]

The Origins of Freemasonry, Scotland’s Century 1590-1710. David Stevenson

Cambridge University press 1988 Page 166

[viii]

Letters of Sir Robert Moray to the earl of Kincardine 1657-73. David

Stevenson Ashgate Publishing Co 2007 pages 5, 91, 113

[ix]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 24

[x]

Correspondence of Sir Robert Kerr, first Earl of Ancram, and his son William,

third Earl of Lothian. by Robert Kerr, Edinburgh

[Printed by R. & . R. Clark] 1875. Page 142

[xi]

A short abridgement to Britane’s distemper. Patrick Gordon, Spalding Club

1844 Pages 5-6

[xii]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 9

[xiii]

Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Times, by Gilbert Burnet; Martin

Joseph Routh; Thomas Burnet, et al;Clarendon Press Oxford 1823 Pages

39-43

[xiv]

The General biographical dictionary by Alexander Chalmers Printed for J.

Nichols London, , 1812-(1816) Pages 341-342

[xv]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Pages 13-20

[xvi]

Dictionary of National Biography by Sir Leslie Stephenson,

Published Oxford University 1885 Pages 227-230/ The

concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions of England, Scotland, and Ireland

1639-1660” Stephen C. Manganiello, Rowman

& Littlefield Publishers,

Inc.2004 pages 359-361

[xvii]

Henrietta Maria by Henrietta Haynes Methuen & Co. London 1912

Pages 197

[xviii]

Ibid pages 194-200 / A short history of

England and the British Empire, Laurence M. Larson, Henry Holt & Co. 1915

Page 350

[xix]

Henrietta Maria by Henrietta Haynes Methuen & Co. London 1912

Pages 199

[xx]

Antiquities of Strathhearn . . . John Shearer, Jr. Crieff,

D. Philips, 1881. Pages 85-88

[xxi]

Papers of Thomas Murray,

1593-1623, at Lambeth Palace Library, London

[xxii]

The Memoirs of James Marquis of Montrose. Rev George Wishart, translated by

Rev A.E. Murdoch Longmans Green & Co. 1893 Page 41

Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Times, by Gilbert Burnet; Martin

Joseph Routh; Thomas Burnet, et al; Clarendon Press Oxford 1823

Page 102

[xxiii]

The Autobiography of Anne Halkett.

Anne

Halkett, John Gough Nichols 1875 Introduction

[xxiv]

Sir Kenelm Digby gentleman of the Bedchamber of King Charles the First,

written by himself, Saunders & Otley, London 1827 (reprinted by Kessing

Publications 2006) Introduction page xxxv; :Court Patronage & corruption

in Early Stewart England, Linda Levy Beck, Routledge, London 1993, Page 45-56,

:King Charles I Pauline Greg, University of California Press, 1984, page 121,

:Progresses, Processions and Magnificent, of King James the First, John

Nichols, Printed by and for J.B. Nichols, London, 1828, page 222

[xxv]

Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Times, by Gilbert Burnet; Martin

Joseph Routh; Thomas Burnet, et al; Clarendon Press Oxford 1823 Page

36-37

[xxvi]

New General Biographical Dictionary, Rev. Hugh James Rose, B.D. Vol. X. B.

Fellowes, Ludgate Street London. 1853. Page 210

[xxvii]

Military Leadership in the British Civil Wars, Stanley D.M. Carpenter,

Routledge 2005 Page 184

[xxviii]

New General Biographical Dictionary, Rev. Hugh James Rose, B.D. Vol. X. B.

Fellowes, Ludgate Street London. 1853.

Page 210

[xxix]

Fairfax Correspondence Vol. II Edited by George W.

Johston, Richard beltly, London 1848, Pages 10-12

[xxx]

The Covenanters A History Of The Church In Scotland From The Reformation To

The Revolution, Volume I, James King Hewison, John Smith And Son Glasgow, 1908

Page 353

[xxxi]

Letters of Sir Robert Moray to the Earl of Kincardine 1657-73. David Stevenson

Ashgate Publishing Co 2007. Introduction

page 5 note 10.

[xxxii]

History of the Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary's Chapel) No. 1, David Murray Lyon ,

W.Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh 1873, Pages 79-81

[xxxiii]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 13

[xxxvi]

Letters of Sir Robert Moray to the Earl of Kincardine 1657-73. David Stevenson

Ashgate Publishing Co 2007. Introduction

page 7

[xxxvii]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 32

[xxxviii]

The East Neuk Of Fife, Its History And Antiquities, Second Edition, Rev.

Walter Wood, Edinburgh: David Douglas.1887 Page 217, 219.

[xxxix]

The History of the University of Edinburgh: Alexander Bower Printed for

Oliphant, Waugh and Innes; [etc.] 1817-30. Page 356

[xl]

Letters of Sir Robert Moray to the Earl of Kincardine 1657-73. David Stevenson

Ashgate Publishing Co 2007. Introduction

page 7 note 17.

[xli]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans Green & Co 1922 Page 32

[xlii]

The Diplomatic correspondence of Jean du Montereul: Translated by J.G.

Fotheringham Scottish History Society 1898 Page 13-17

[xlvi]

History of the Great Civil War. Vol. 3. 1645-1647. Samuel Rawson Gardiner.

Windrush edition 20002 London

Page 12

[l]

Encyclopaedia Britannica ... edited by Hugh Chisholm, Vol.. XXXIV, 11th

Edition. The Encyclopaedia Britannica Company 1911 Page 613

[lii]

Letters of King Charles I to Queen Henrietta Maria. Editedby John Bruce, The

Camden Society Printed by J. Nichols & Sons London 1856

Pages 3&4

[liii]

History of the Great Civil War. Vol. 3. 1645-1647. Samuel Rawson Gardiner.

Windrush edition 2002 London Page

62-63

[liv]

Letters of King Charles I to Queen Henrietta Maria. Editedby John Bruce, The

Camden Society Printed by J. Nichols & Sons London 1856

Pages 14-15

[lv]

The chief actors in the

Puritan revolution. Peter Bayne, J. Lewis & Co., 1879 pages

136-137

[lvi]

Letters of King Charles I to Queen Henrietta Maria. Editedby John Bruce, The

Camden Society Printed by J. Nichols & Sons London 1856

Pages 19-20

[lvii]

The Origins of Freemasonry, Scotland’s century 1590-1710. David Stevenson,

Cambridge University Press 1988 Page 186

[lviii]

The Diplomatic correspondence of Jean du Montereul: Translated by J.G.

Fotheringham Scottish History Society 1898 Page 148

[lxii]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 42

[lxiii]

Letters of King Charles I to Queen Henrietta Maria. Editedby John Bruce, The

Camden Society Printed by J. Nichols & Sons London 1856

Pages 29-30

[lxiv]

The Diplomatic correspondence of Jean du Montereul: Translated by J.G.

Fotheringham Scottish History Society 1898 Page 180

[lxv]

Letters of King Charles I to Queen Henrietta Maria. Editedby John Bruce, The

Camden Society Printed by J. Nichols & Sons London 1856

Pages 36

[lxvii]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 49

[lxviii]

History of the Great Civil War. Vol. 3. 1645-1647. Samuel Rawson Gardiner.

Windrush edition 2002 London Page

97-102

[lxix]

Letters of King Charles I to Queen Henrietta Maria. Edited by John Bruce, The

Camden Society Printed by J. Nichols & Sons London 1856

Pages 63

[lxxii]

Burnets Lives of the Hamiltons, Gilbert

Burnet Oxford University Press 1673, page 373

[lxxv]

Burnets Lives of the Hamiltons, Gilbert

Burnet Oxford University Press 1673, page 374-389

[lxxvi]

The Hamilton Papers Samuel Rawson Gardiner, Printed for the Camden Society,

1880. page 118

[lxxvii]

History of the Great Civil War. Vol. 3. 1645-1647. Samuel Rawson Gardiner.

Windrush edition 2002 London Pages

182-186

[lxxviii]

Letters of King Charles I to Queen Henrietta Maria. Editedby John Bruce, The

Camden Society Printed by J. Nichols & Sons London 1856

Pages 85

[lxxix]

The Hamilton Papers Samuel Rawson Gardiner, Printed for the

Camden Society, 1880. page 136

[lxxx]

History of the Great Civil War. Vol. 3. 1645-1647. Samuel Rawson Gardiner.

Windrush edition 2002 London Page

186

[lxxxi]

Lives of the Hamiltons, Gilbert

Burnet Oxford University Press 1673, page 391

[lxxxii]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 55

[lxxxiii]

The Diplomatic correspondence of Jean du Montereul: Vol.2 Translated by J.G.

Fotheringham Scottish History Society 1898 Page 16-17

[lxxxv]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 57

[lxxxviii]

The lives of the English regicides, and other commissioners of the pretended

High court of justice, appointed to sit in judgement upon their sovereign,

King Charles the First. Mark Noble, J. Stockdale, London 1798 Pages 281-287

[lxxxix]

The life of Sir Robert Moray, Soldier, Statesman and Man of Science. Alexander

Robertson Longmans green & Co 1922 Page 60

|

![]() News Feed |

News Feed |  Subscribe News by Email

Subscribe News by Email