|

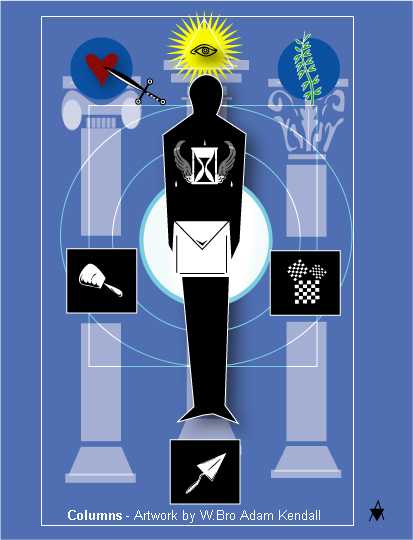

Part

One: An Introduction to Masonic

Aestheticism

The

intent and action of the individual

will that compels one to enter the portals of Freemasonry and the ongoing

process by which one shapes himself as such is a common theme throughout the

tradition. It is illustrated by the

symbolism and allegory of the craftsman's aesthetics,

which is defined as a branch of philosophy dealing with the nature, creation,

and appreciation of beauty. Indeed,

the whole of the Masonic mythos is said to impart into the initiate the creative

skills of ancient temple builders in order that their speculative discipline

blossoms into self-exploration. Hence

the symbology, ritual drama (or allegory), jargon and (especially) the common

origins Masonic history—both of ancestral builders and medieval architects and

workers of stone, mortar and metal-- is the central theme of the instructional

dramas that comprise Ancient Craft Freemasonry.

It

has been my personal observation as an artist, that the method of teaching

embodies a systematic ritualized illustration of real aesthetic principals derived from a

mythological operative past. The

path of the aesthete, an admirer of

aesthetic principles, is not limited to only artisans, but to all people good

and true who are interested in the key precepts of Wisdom, Strength and Beauty.

Freemasonry’s ingenious and layers-deep system of rectitude and

self-knowledge teaches, at its core, that an individual can build and lead their

lives as if it were metaphorically a beautiful, strong edifice—shaped with

skill, but, alas, not without the least effort or exertion of regulated force

and restraint. Herein lays the

necessity of training a technique that requires a natural predisposition to a

creative and rational mindset. Were this philosophy devoid of appreciation for the

supra-conscious and spiritual part of man, it would be rigid and devoid of the

mechanics that encourage the development of creative possibilities.

Conversely, if it was purely creative for its own sake, the effort would

be deemed unfocused, no matter what the design. For

the arts in all of their forms: the scientific; the medical; the architectural,

and the Fine; all combine formula, intellect, logic, and reason with mercurial

intuition and creativity. These professional arts are also are dependent upon

each other-- for many buildings would never be erected without the metallurgist

or other scientists, such as an engineer or seismologist to determine the finer

points of the building’s structure and its relationship to the earth on which

it sits. Moreover, none of them can

be expressed without the skills of the fine artist who may draw the anatomy of a

building or a body to use as a map for the architect or surgeon. In fine, aestheticism

is the ideal by which all skills of the human being may unite to create a work

of art in perfect harmony. This is

a very important point when considering the unity and interdependence in nature.

Intent

and action must be balanced in order to reach its

goal--which is to create something, as mentioned before, balanced and perfect.

However, the end result is not the finality; the process of its creation

determines its perfection. Therefore

to the aesthete, the process of understanding the path and the way one may

affect the unfolding of its becoming, lies in the patient acquiring and exercise

of skill-- which is the harmony of intent and action.

Part

Two—The Rough and Perfect Ashlars

In

Freemasonry, one set of symbols that exemplify the aesthetic principles of

determining and evoking the potential in art and livelihood is the Rough and

Perfect Ashlars. They are a class of symbols surprisingly overlooked in some

jurisdictions, which seems strange considering Freemasonry concerns itself with

the very subject of building in stone! It

is a class of symbols whose equation and sum have an important mention in all

degrees of the Craft Lodge, primarily in the Entered Apprentice, the Fellow

Craft; but also within the degrees of Mark Master Mason and the Royal Arch.

The ashlars are actual objects to be shaped and fit by the stonemason,

just as they are symbols of the aesthetic process of creation, which includes at

every point the balance of technical skill of every successive degree or level

of understanding. By shaping the

ashlar from a state of roughness (that is, pure potential) to something

beautiful and potential manifest—not just merely useful-- the intent

and action of its creator’s intellect and creativity may be determined.

The

Rough Ashlar is a rough stone cut and raised from the quarries by the

Apprentices under the supervision and experience of the Fellowcrafts and the

watchful eye of the overseers, or Masters, and is thus explained by the Bro.

Johann Christian Gadicke in his Lexicon of

Freemasonry:

The

Rough Ashlar is a rough stone cut and raised from the quarries by the

Apprentices under the supervision and experience of the Fellowcrafts and the

watchful eye of the overseers, or Masters, and is thus explained by the Bro.

Johann Christian Gadicke in his Lexicon of

Freemasonry:

“We

cannot regard the rough ashlar as an imperfect thing, for it was created by the

Almighty Great Architect and he created nothing imperfect, but gave us wisdom

and understanding, so as to enable us to convert the seemingly imperfect to our

especial use and comfort. What

great alterations are made in a rough ashlar by mallet and chisel!

With it are formed, by the intelligent man, the most admirable pieces of

architecture. And man, what is he

when he first enters into the world? —Imperfect, and yet a perfect work of

God, out of which so much can be made by education and cultivation.”

Notice

the mention of the tools of the first degree—the mallet, (the common gavel),

and the chisel (which is not included in California Preston-Webb ritual for the

Entered Apprentice, but exists in various English and Continental European

workings). Indeed, this chisel

should be considered a very important tool even in our Preston-Webb work, in

relation to the 24-inch gauge—for both are the handmaidens of the gavel

without which it would be a mere instrument of force. By a regulated blow from

the mallet (or gavel), with the guidance of measurements set by the gauge, the

chisel may make its cuts made by the skilled craftsman.

From the use of skill and intelligence as stated by Gadicke one can

deduce how these tools would be helpful. Meditation

and thought on these symbols are required by the speculative craftsman so as to

derive the beautiful allegory of their use in order to give a place in one's

personal mythology.

Consider

the definition by Robert Macoy of the Perfect Ashlar which has become a perfect,

squared stone that symbolizes our unconscious and conscious essence fitted for

the builder’s use in “that house made not with human hands”:

“The

Perfect Ashlar is a stone of a true square, which can only be tried by the

square and compasses. This

represents the mind of a man at the close of life, after a well-regulated career

of piety and virtue, which can only be tried by the square of God’s Word, and

the compasses of an approving conscience.”

“The

Perfect Ashlar is a stone of a true square, which can only be tried by the

square and compasses. This

represents the mind of a man at the close of life, after a well-regulated career

of piety and virtue, which can only be tried by the square of God’s Word, and

the compasses of an approving conscience.”

As

per Macoy, it would seem that the perfection of the ashlar is a result of

applying the aesthetic principal that will draw forth the stone's true beauty by

first recognizing its inherent goodness and perfection, and by peeling

away the layers to expose its inner nature. This unveiling of true potential

is made manifest by a long and sometimes arduous road; the process requires

knowledge coupled with knowledge intuition or faith, that is, creativity. The speculative mason learns the manner by which his

technique and creativity combined and perfected through degrees or equations

assist him in developing latent creative powers.

Today

in California lodges are re-adopting the use of the ashlars and placing them

side by side in the East. A number

of traditions, particularly on the European Continent, also accord both ashlars

an important place in the East, but with interesting differences in their

arrangement, which alludes to their purpose in ritual-- of whose definition we

can clearly benefit. In some German

Masonic rituals, for example, the rough is situated on the first step to the

dais of the Worshipful Master. The

perfect ashlar is placed on the second step, which symbolizes its relationship

with the duties and tasks of the Fellow Craft--to use the perfected stone as a

measure by which his tools are trued. If

one follows the second degree in the American rituals, the same deduction can be

made.

It

is by the hewing of the rough stone to its smooth and perfected state so it may

fit perfectly in the building, and that by it all tools may be trued and kept

aright for continued use in our lifetimes.

Thus, this perfect stone becomes to our speculative profession a symbol

of the greatness of the virtue that was born from the rough state by the skilled

determination of the craftsman to its true potential as a useful part of the

whole.

By

considering this beautiful class of symbols interdependent with the working

tools of every degree in Freemasonry, one may begin to develop a deeper attitude

in regard to our Craft: recognition of the aesthetic approach is necessary in

order to properly develop the skill in one's life.

The aesthetic principal lends to skill a particular quality of

personality--without which a proper development of our character would be

impossible, or at least produce flawed and unfeeling traits in the individual.

Embracing aesthetic beauty creates for the Freemason level foundations of

an enlightened and intelligent morality by which one will stray to no extreme,

but rather walk softly on a path of balance and mildness.

On

this path, the interplay of force and support combine to hold the frame aloft. Using faith combined with ingenuity, creativity, and the

willingness to go further, one can utilize this symmetry to create one’s own

life into a temple. This

evolutionary process is embodied in the definition of beauty. Thus, perhaps it can be said that beauty is eternal and ever

unfolding, as is our knowledge of what is Divine. This is aestheticism as practiced by all artists and brought

forth by the knowledge of their craft.

|

![]() News Feed |

News Feed |  Subscribe News by Email

Subscribe News by Email