My masonic pedigree, while not

particularly unusual, has resulted in many discussions with fellow masons

concerning the origins of Freemasonry and the reasons for variations in masonic

ritual. A member of the Order of DeMolay since I was 14, I petitioned for the

degrees as soon as my twenty-first birthday drew near. As a Lewis

I was allowed to submit my petition before coming of age, and I was initiated

less than a month following my twenty-first birthday. Being on leave from the

U.S. Navy, I was initiated and passed in my home lodge, but was raised as a

courtesy candidate in another state.

At

a lodge I visited one night, an officer of many years standing noticed that I

would be helping out with the degree work and introduced himself to me. He

asked about my home lodge and I told him about my receiving the first two

degrees in Ohio, but the third in Virginia. He replied that he’d originally come

from another state, where the work was quite a bit different than Ohio’s, and

how this sometimes presented a challenge to him in his ritual work, even though

he’d been in Ohio now a number of years. I said I had the same problem, having

been active in Virginia for two years before getting out of the Navy.

At

a lodge I visited one night, an officer of many years standing noticed that I

would be helping out with the degree work and introduced himself to me. He

asked about my home lodge and I told him about my receiving the first two

degrees in Ohio, but the third in Virginia. He replied that he’d originally come

from another state, where the work was quite a bit different than Ohio’s, and

how this sometimes presented a challenge to him in his ritual work, even though

he’d been in Ohio now a number of years. I said I had the same problem, having

been active in Virginia for two years before getting out of the Navy.

And

then it happened. Confident and self-assured, the brother said, “Oh, that’s

Southern Jurisdiction.”

I

had heard variations of this comment many times, usually along the lines of,

“Oh, they’re Ancient, Free &

Accepted.” These remarks had always troubled me, so I answered, “Well, Southern

Jurisdiction only applies to Scottish Rite.” To which the brother gave the

condescending response, “Don’t kid yourself, son. All grand lodges have

different rituals.” Stunned, I was just about to follow up when the Master

called for the brethren to clothe.

I

have been advised by brother masons that Southern/Northern Jurisdiction and F.

& A.M./A.F. & A.M. designations account for differences in lodge or

ritual practices on more occasions than I care to remember. Usually such

pronouncements are made with a gravity which brooks neither disagreement nor

discussion. Knowing the importance of looking for the good in things, I try to

remind myself that I have yet to hear anyone tell me “that Masonry in its

present form started in remote antiquity.”

Believe

it or not, this does happen. Bro. Harry Mendoza, a respected masonic historian,

gave a talk at an English lodge once. As he tells it,

My paper dealt with some of the phrases we use today – and one

of them was ‘from time immemorial.’ I said that Freemasonry as we know it today

stretched back no more than about 600 years, though some would argue 250 years.

A Grand Officer present – of some years’ seniority – stood up and said that he

couldn’t really allow that; I was misleading the brethren. Masonry, he declared

firmly, was of time immemorial; it

went right back to the time of Noah – and there were degrees to prove it!”

I

believe such statements reveal a need for more-focused masonic education

programs, programs aimed at basic misconceptions about the Craft, its

structure, and its history. What should be the goals of such a program? Several

come to mind, though in no particular order.

Our Origins – Separating Fact from Fiction

1. Compare and contrast traditional or ritualistic history, historical theories,

and scholarly historical research.

Traditional/ritualistic

history dates Masonry from Adam, and includes the story of Hiram Abif and the

Lost Word. The story of Hiram Abif is not biblical, nor does everything in

Freemasonry come from the Bible, as I have heard claimed more than once.

Sources of traditional history include such things as the Old Charges and the

ritual.

Traditional history is not history in the true sense of the word, being for the

most part fanciful products of the imaginations of various writers. When found

in the ritual, such accounts are meant to teach concepts of morality, not to

give an accurate portrayal of past events.

Historical

theories, only sometimes supported by valid research and investigation, range

from the operative-speculative transition theory, championed by Robert Freke

Gould and Harry Carr, to the monastic inner sancta theory, proposed by Cyril

Batham.

Both of these are theories about the origin of speculative Freemasonry. It

should be stressed that no one today really knows how the Fraternity

originated, but the transition theory seems to have taken on a life of its own,

and is too often treated as the last word on the subject.

It should be stressed to our students that these are but theories of origin and

not established facts.

Scholarly

historical research requires reliable methods of investigation and inquiry.

Such works identify opinions and theories as such, provide citations for source

materials, rely on direct evidence where possible instead of hearsay, do not

make unwarranted pronouncements or implied assumptions, and are not subject to

credible attack as to their methodology.

Lodge

education officers should both understand for themselves and clearly identify

to others which portions of a program are based on fact, theory, or traditional

history. Theories based on poor scholarship should be discouraged in official

education programs, or at least properly identified. Lets avoid teaching

parables as history.

2. Talk about masonic research,

particularly about the publications of The Masonic Service Association, Quatuor

Coronati Lodge, the Scottish Rite Research Society, the Masonic Book Club, and

other reputable sources. Advise masons where to locate masonic books, providing

names, addresses, and telephone numbers for various publishers. Indicate that

the popularity of a book (e.g., Born in

Blood) or writer (e.g., Arthur

Edward Waite) indicates

neither soundness of the theories espoused, validity of the conclusions made,

nor qualifications of the author. A one-year subscription to The Short Talk Bulletin should be given

to every mason with his first dues card. A new mason could do a lot worse than

to begin his study of Freemasonry by reading Carl H. Claudy.

Organization and

Regularity

3. Instruct masons on the structure of

American Freemasonry. Make sure new masons understand that although there is a

place in the Fraternity for the concordant and appendant bodies, the Grand Lodge is the ultimate governing

authority over the Craft,

there is no higher degree than that of Master Mason, and the attraction of the

side degrees should be viewed in its proper perspective.

Impress upon masons that the jurisdictional arrangements of the Scottish Rite

and other such bodies have no relevance to U.S. grand lodges nor to U.S. Craft

(blue lodge) Masonry in general. Furthermore, make it clear that neither the

location of a state on the map nor the designation of a grand lodge as F. &

A.M. or A.F. & A.M. has any bearing on grand lodge regularity. Nor do such

designations of themselves reveal anything about a grand lodge’s parentage or

pedigree.

4. Explain that the U.S. structure of

Masonry does not obtain in other countries. Explain that in some countries the

Craft degrees are under the jurisdiction of the Scottish Rite (or Ancient and

Accepted Rite), while in others (e.g.,

Sweden), the grand lodge directly controls advancement to degrees beyond that

of Master Mason. Explain that advancement in many parts of the world to the

next degree (starting with the Fellowcraft) is neither fast nor automatic, the

candidate having much more study to do than is usual in the United States.

Further, explain that some grand lodges (e.g.,

Sweden) limit masonic membership to Christians, though this is not the case in

the U.K. or the U.S.

5. Explain that Freemasonry in the United

States is not a Christian organization and that a brother called on to give a

non-ritual prayer at a masonic function should not use words such as “In

Christ’s Name” as doing so could well be offensive to non-Christian masons who

may be present. It would

seem the better path to keep non-ritual prayers on a basis “in which all men

agree” as the old charges suggest.

6. Tell of the controversies which gave

rise to the Antients grand lodge, which then labeled the first grand lodge as

“Moderns,” what the basic causes of the difficulties were, and how the two

grand lodges settled their differences and formed the United Grand Lodge of

England. Explain

that masons traveling to foreign countries may expect to find different

passwords in use (including the S.),

as well as different sets of working tools, different ways of presenting the

legend of the third degree, different GHSs, and other general differences

around the world, particularly between the more popular post-Union rituals used

in Britain and the Webb rituals used in the United States.

Explain that in some parts of the world (and the U.S., too) the Craft degrees

are worked using rituals propounded by the Scottish Rite.

Discuss the “Baltimore” Conventions of 1842, 1843, and 1847 and how they

affected American Freemasonry,

in part by launching the trend for lodges to transact business only on the

third degree and curtailing development of a general grand lodge for the United

States.

7. Explain Prince Hall Masonry.

Point out that black and Prince Hall masons are not necessarily irregular, that

irregular black and Prince Hall masons are not irregular because of race, that

a black mason is not necessarily a Prince Hall mason, and that many black

masons belong to lodges chartered by so-called “white” grand lodges.

Irregularity stems from a grand lodge’s pedigree, not the racial makeup of its

lodges, and is, in any case, always judged subjectively.

The Ritual

8. Explain in general terms the history of

masonic ritual. The

original masonic degrees were Apprentice and Fellow. The Master Mason degree

was more or less settled in the 1720s

and the Royal Arch arose in the 1730s,

but all other degrees are more recent innovations and arose outside of the

Craft Masonry setting.

Grand lodges have sovereign authority to determine what Craft rituals will be

used in their jurisdictions. A grand lodge may specify a particular ritual, or

may leave the matter up to local lodges and simply set general guidelines.

The designations “F. & A.M.,” “A.F. & A.M.,” “F.A.A.M.,” or otherwise

are irrelevant as far as ritual is concerned.

9. Explain the origin of the words, “So

mote it be,” being Middle English for “So may it be” or “So be it,” and

appearing twice in the Regius Manuscript.

Provide new masons with a properly translated copy of the Regius MS and suggest

that they read John Hamill’s book, The

History of English Freemasonry.

10. Explain that masonic ritual is supposed

to make sense spiritually and emotionally, not logically or historically. Take,

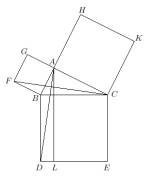

for example, the Pythagorean theorem, which relates the lengths of the sides

of a right triable to its hypotenuse, stated algebraically as a2+b2=c2.

Mathematical historians dispute whether Pythagoras himself ever posited

the theorem named for him – or devised a proof of it. But in either case, the

Babylonians made use of the theory by about 2,000 B.C., some 1,400 years before

Pythagoras was born. Nothing survives of Pythagoras’ work, although the

“bride’s chair proof” or “proof walking on stilts” as it has been called,

popularized by Euclid and shown on masonic tracing boards, is as good a

representation as any of how the early Greeks would have approached the

problem. The proof

is used as the Past Master symbol by our English brethren.

10. Explain that masonic ritual is supposed

to make sense spiritually and emotionally, not logically or historically. Take,

for example, the Pythagorean theorem, which relates the lengths of the sides

of a right triable to its hypotenuse, stated algebraically as a2+b2=c2.

Mathematical historians dispute whether Pythagoras himself ever posited

the theorem named for him – or devised a proof of it. But in either case, the

Babylonians made use of the theory by about 2,000 B.C., some 1,400 years before

Pythagoras was born. Nothing survives of Pythagoras’ work, although the

“bride’s chair proof” or “proof walking on stilts” as it has been called,

popularized by Euclid and shown on masonic tracing boards, is as good a

representation as any of how the early Greeks would have approached the

problem. The proof

is used as the Past Master symbol by our English brethren.

Nor

is Pythagoras famous for saying “Eureka,” meaning “I have found it.” It was

Archimedes who gave this exclamation when, sitting in his bath, he realized how

to determine whether the crown of Hieron II, King of Syracuse, was pure gold by

immersing it in water to discover its specific gravity. Pythagoras was not, of

course, “raised to the sublime degree of Master Mason.” There was no such thing.

11. Foster an interest in quality ritual and

encourage establishment of lodges of instruction. The cipher ritual is not a

substitute for rehearsals and must not be used as a crutch. A lodge of

instruction could, by bringing together members of several lodges to practice

jointly, promote exchange of good ideas and discourage unnecessary practices

and bad habits. Ideas abound: teach deacons and stewards how to hold and carry

a staff properly; teach chaplains how to time their prayers and direct them to

the candidate; teach proper voice techniques; teach speakers how to deal with

unexpected situations (e.g., an

improperly prepared EA candidate being presented to the Master). There are two

areas where lodges of instruction could be especially helpful: demonstrating

proper salutes, and teaching correct pronunciation and delivery.

Due-guards

and signs. When I joined the Navy, I was told that salutes become

sloppier in direct proportion to the rank of the officer giving them. In

Freemasonry, however, where our only contention should be on “who best can work

and best agree” (i.e., make their

wall level and plumb), just the opposite should be true. Unfortunately it is

not. Due-guards and signs should be given in a crisp, military manner, and

accompanied by appropriate placement of the feet. Hands should be completely

flat for all due-guards and signs, except for the moving hand in the FC sign.

For

some unknown reason, the FC degree presents special problems. There is a

disturbing tendency in some lodges to give the FC due-guard with the one arm

extended. This is not correct! The

resulting gesture has no place in a masonic lodge. All signs, including the FC

sign, being p. signs, represent a ctg m and not

a plg m. We are not talking dolls, nor are we throwing salt or catching flies.

Word

pronunciation and delivery. I am reminded of the story of the new mason

who went home and told his wife of the three types of men to be found in a

masonic lodge: the walkers, the talkers, and the holy men. The walkers walk

around the lodge; the talkers talk while the walkers walk; and the holy men

(they’re the ones with aprons trimmed in purple), they sit with their heads in

their hands saying, “Ohmigod.”

Of

course it’s easy to preach from behind; its quite another when you’re sitting

in the East with all eyes upon you. We all acquire bad habits – some very dear

to the heart. In fact, certain passages sound better with a word pronounced, shall we say, “with improvement.”

For example, I much prefer /DAY-i-tee/, /PILE-as-tur/, and /DYE-ves-ted/. All of which are wrong. Mispronouncing the

word “divest” is particularly popular because emphasizing the first syllable

draws attention to the distinction between

investing and divesting.

Which proves the point that we must consider the message being conveyed not

only by the words but by their delivery as well. Correct pronunciation is only

a beginning, but it is a necessary one.

Before

moving on, allow me to suggest three areas where a zero tolerance policy should

be employed and absolute perfection demanded: the apron presentation, the “G”

Lecture, and the presentation and description of the FPOF. These areas are

the hearts of their degrees. I believe that anything less than perfection in

their presentation is an insult both to the candidate and to the lodge.

So

let’s pronounce the words right. When they’re said wrong, the speaker comes

across as uncaring and un-prepared. Let’s understand the meaning, too, because

correct pronunciation will not save a speaker who doesn’t know what he’s

saying.

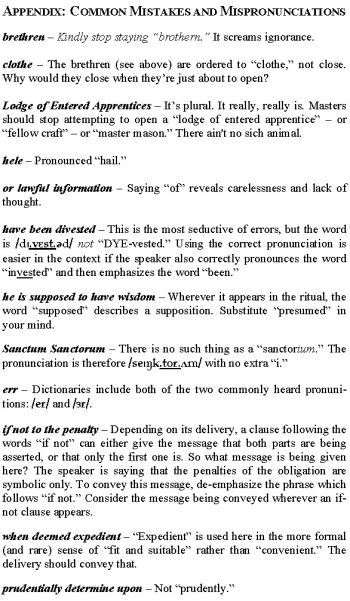

Some

word usages (“stone,” “bourne,” “smote”) are commonly heard only in masonic

ritual. I would like to touch on these and the more common offenses which so

often arise, but I must leave a more thorough study for the future. A number of

problem words are listed in the Appendix.

So

much for ritual matters.

Mythconceptions

12. Advise

masons that Freemasonry is not anti-Catholic although, depending whom you ask,

the opposite may be true.

In

1974 Cardinal Seper wrote to the bishops, stating that “The Sacred Congregation

for the Doctrine of the Faith . . . has ruled that Canon 2335 no

longer bars a Catholic from membership of masonic groups. . . . And so a

Catholic who joins the Freemasons is excommunicated only if the policy and actions

of the Freemasons in his area are known to be hostile to the

Church. . . .”

But there have been developments since then.

In 1983, a new Code of Canon Law was published, wherein

Canon 2335 was replaced by Canon 1374, which only forbade membership in

organizations which “plot against the Church” and removed the penalty of

automatic excommunication, replacing it with “a just penalty.” This is in

conformity with Cardinal Seper’s interpretation. Shortly before the new Code

was published, however, the Sacred Congregation, under a new Prefect, issued a

pronouncement that Canon 1374 did not really affect the original policy.

Although the pronouncement nullifies Cardinal Seper’s earlier ruling, it was

issued prior to the effective date of the new canon. Accordingly, some dioceses

are holding that the canon supersedes the ruling and are on that basis

permitting masonic membership.

The

point is that masonry is neither “for” nor “against” any faith or denomination.

The repeated need to say so is deeply troubling as it reveals, at best,

questions arising out of on little or no capacity for independent thought.

13. Explain that the American Revolution was

not a masonic plot or conspiracy,

nor was the Boston Tea Party,

and suggest that masons curb their appetite for these stories. Certainly masons participated in all these events,

but if Masonry as an organization were to have done so it would be more cause

for shame than jubilation. After all, General Arnold was also a freemason.

Attending to the Gullible – and the Hateful

14. Discuss the Morgan Affair, and explain

the danger of ignoring anti-masonic sentiments.

Masons are charged not to let their zeal for the Institution lead them into

argument with those who through ignorance may ridicule it. But anti-masons are

not acting only out of ignorance. Their attacks are not ridicule but weapons

specifically employed to destroy society’s greatest champion of freedom of

conscience and universal morality.

Masons should be strongly encouraged to study Ed King’s website at http://masonicinfo

.com. It provides a wealth of information about the anti-mason and

his motivations.

15. Explain that Freemasonry isn’t about

secrets, and that “It’s a secret” is an unacceptable response to general questions

about the Craft. Anti-masons like to attack the straw-man of masonic “secrecy,”

attempting thereby to neatly avoid the fact that our organization, like any

other, is entitled to its privacy. As if we should be ashamed of restricting

our meetings to members only!

Make sure masons understand that “[t]he [real] secrets in

Masonry are personal insights. They are secret not because we are pledged to

conceal them, but because they cannot be truly communicated from one person to

another.” Anti-masons

who think they’ve done something clever by publishing what they believe to be

our “secrets” are truly a sad lot. An unexpected writer (Giovanni Casanova) put

it this way:

Men who plan only to be accepted as Freemasons with the purpose

of coming to know the secret of the Order run great risk of growing old under

the trowel without ever attaining their object. [There is] a secret, but it is

so inviolable that it has never been told nor confided to anyone. Those who

grasp at the superficiality of things believe that the secret consists in

words, signs and grips, or that in the final analysis it is the grand word of

the last degree. A mistake!

He

who discovers the secret of Freemasonry, for they never know where they are

finding it, will not arrive at that knowledge by reason of frequenting lodges.

He gains it only by the strength of reflecting, of reasoning, of comparing, and

of deducing. He will not confide it to his best friend in Freemasonry, for he

knows that if that brother does not find it for himself as did he, the friend

will not have the talent to extract the means to do so from what shall be said

in his ear. * * *

[T]hose who by dishonest indiscretion make no scruple of

revealing what is done [in lodge] have never revealed the essential: they do

not know it, and if they have not known, truly they cannot reveal. . . .

Unfortunately,

masonic history and many of the matters above are also not learned by

“frequenting lodges.” But unlike the secrets of the apron, square, compasses

and trowel, masonic education can be

taught – and we are the ones charged to do so.

Conclusion

Six

hundred years ago, an anonymous priest, for his masonic education project,

wrote:

This good lord

loved the craft full well,

and proposed to strengthen it, every dell;

For diverse faults

that in the craft he found,

he set about into the land

After all the

masons of the craft,

to come to him full even straghfte

[straight].

For to amend these

defaults all,

by good counsel, if it might fall,

An assembly then he

could let make,

of diverse lords in their state --

Dukes, earls, and

barons also;

knights, squires, and many mo.

(And the great

burgesses of that city,

they were there all in their degree.)

These were there

each one algate [everywhere, always],

to ordain for these masons’ estate --

There they sought

by their wit,

how [that] they might govern it:

Fyftene artyculus þey þer

sow3ton,

and fyftene

poyntys þer þey wro3ton.

My

fifteen points are nothing compared to the timeless message of the Regius

Manuscript. But I flatter myself that my points also have their place. I’ve

been told that the trouble with masonic education of this type is that it never

reaches the brethren who need it most – that is, the ones who believe that

their long tenure in lodge equals knowledge of the Craft. This is alarming,

because as the saying goes, “If you think education is expensive, try

ignorance.” These harm us and no one else, and cry out for good counsel to be

whispered in a brother’s ear.

I

know that I’m preaching to the choir. But who else is there to call on? A more

aggressive masonic education program will work – if we work it. It is essential to raise the level of knowledge

on which the average mason stands. I pray the Craft to correct these

misconceptions wherever found, to examine the content of our education

programs, to continue being leaders and shining a brighter light into the

darkness of unconsidered speculation and hearsay which too often passes for

knowledge in our mystic circle.

|

|

|

Bibliography

The bibliography

has been incorporated into the notes.

The author thanks the

following persons for their comments and suggestions, all of which have contributed

to this work. In alphabetical order --

Wor. Bro. James G. Bennie, WM,

Lodge Southern Cross No. 44, F. & A.M., British Columbia

Wor. Bro. Greg M. Glur, PM,

Shiloh Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M., North Dakota

Bro. Karl-Gunnar Hultland, FC,

Saints John Lodge Ultima Thule, Swedish Order of Freemasons

Lisa J. Kiser, Ph.D., Professor

of Old English and Middle English Literature, English Linguistics, and History

of the English Language, The Ohio State University

Wor. Bro. Den Robinson, PM, Sant

Beuno Lodge No. 6733, A.F. & A.M., England

Wor. Bro. Richard D. Snow, PM,

New England Lodge No. 4, F. & A.M., Ohio; PM, Ohio Lodge of Research

Wor. Bro. Timothy B. Strawn, PM,

New England Lodge No. 4, F. & A.M., Ohio

Wor. Bro. Robert L. Tucker, PM,

Adoniram Lodge No. 517, F. & A.M., Ohio

Wor. Bro. Louis S. VanSlyck, PM,

Trinity Lodge No. 710, F. & A.M. of Ohio; PM, Ohio Lodge of Research

|

|

Fyftene artyculus þey þer

sow3ton, and fyftene poyntys þer þey wro3ton. (Fifteen

articles they there sought, and fifteen points there they wrought.) The words 3ower, sow3ton, and wro3ton (your, sought, and wrought)

contain a character called the yogh, which is often mistaken for,

and wrongly transliterated as, a z. The Middle English yogh

was used for two sounds, later inscribed y at the beginning of a word, and gh

elsewhere to indicate the velar-fricative. This shift was underway when the

Regius MS was written. The gh survives silently today in such

words as knight. Pyles, Thomas, and Algeo, John, The Origins and Development of the English Language, pp. 107-108,

139-140 (Third ed., 1982). Old and Middle English also had characters for the

voiced and unvoiced dental fricative th. These characters were called the

eth

(Ð, ¶) and the thorn (Þ, þ)

respectively. Middle English used both characters, as well as th, interchangeably. My favorite words in

the poem: “Kyng Nabogodonosor.”

![]() News Feed |

News Feed |  Subscribe News by Email

Subscribe News by Email