The symbol of

the Skull and Crossbones, often called the Memento Mori, is a grim

reminder of our own mortality. The Latin phrase Memento Mori is generally

interpreted as “Remember that you must die”[i], and is often associated with other fatalistic

expressions[ii]

such as Hora Fugit (The Hour Flees) or Tempus Fugit (Time Flies). The

first Masonic adoption of the Memento Mori appears to have its roots in

the York Rite Chivalric Orders, especially the Order of Malta and the Order of

the Temple. The establishment of these Orders coincides well with the periods in

which the Memento Mori was reaching its zenith as an expression of

Christian belief concerning death and dying. This paper will examine the

evolution of the Memento Mori, its historic representations of death in

the Christian belief system, and its adoption and use by Freemasonry. The reader is asked to be keenly aware that I am writing this

strictly within the context of the Christian tradition; I am of course aware

that many Masons are not themselves Christians, and I do this not out of

religious conceit, but rather out of a need to narrow the scope of my

investigation to that which is manageable in a paper of this type. I

respectfully ask that my perspective not be construed as bigoted or intolerant.

Memento

Mori in Art and Literature

The skull, the

skull and crossbones, and the skeleton were all used extensively in early

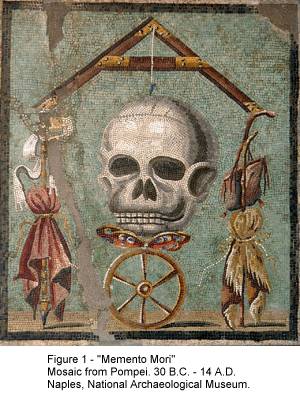

artwork to symbolize death. One particular representation of the skull in

artwork which might be of interest to Freemasons is that found in a tile mosaic

from a tabletop which was retrieved from the ashes of Pompei[iii];

this mosaic includes a skull crowned by an ancient plumb-line, illustrating

death as the great leveler (Figure 1).

The skull, the

skull and crossbones, and the skeleton were all used extensively in early

artwork to symbolize death. One particular representation of the skull in

artwork which might be of interest to Freemasons is that found in a tile mosaic

from a tabletop which was retrieved from the ashes of Pompei[iii];

this mosaic includes a skull crowned by an ancient plumb-line, illustrating

death as the great leveler (Figure 1).

Of

course, not every use of the skull in artwork is related to the symbolism of Memento

Mori. The artistic theme of Memento Mori seems to be coincident with

the onset of the Black Death in Europe (circa 1348)[iv]

in which images of death and references to the certainty of human mortality

begin to appear in mainstream as well as funereal artwork. It is during this

period and the subsequent period extending well into the late 18th

century[v]

that an entire genre of tombstone art evolved which came to be known as cadaver

tombs. These “double decker” styled tombs were sarcophagi that resembled a

stone bunk bed with the deceased shown alive on the top level and in death on

the bottom level. The bottom level image usually showed the deceased en

transi (decayed) in the grave, complete with worms, rot, skeletal remains,

and shroud. Many of these tombs bear inscriptions (epitaphs) which provoke the

reader to consider his or her mortality[vi]:

“Come

nere my friends, behould and see

Suche

as I am suche shall you bee:

As

is my state within this tombe

So

must be yours before the doome

Even

dust as I am now

And

thou in time shall be”

Somewhat related

to Funereal art, sculpture work incorporating Momenti Mori symbolism in

monuments (other than tombs) was also common. Gian Lorenzo Bernini[vii]

was an especially popular Roman sculptor of the 16th and 17th

Centuries who created a Memento Mori monument to Pope Urbanus VIII at St.

Peters (circa 1640 A.D.) and another for Pope Alexander VII (circa 1678 A.D.)

It is said that

the great Michelangelo (1475-1564 A.D.), during the final 20 years of his life

had a Memento Mori (a skeleton with a coffin on its back) painted on the

stairway of his home[viii].

Non-funereal artwork of the period included paintings such as Et-in-Arcadia-ego

(Even in Arcadia, there am I) by the famous Baroque

artist Nicholas Poussin (1594–1665 A.D.)[ix]

portraying a tomb (It is the tomb of Daphnis, a shepherd and inventor of

pastoral poetry) in the mythic paradise of Arcadia. Caravaggio (circa 1607) in

his St. Jerome Writing notably includes a Death Head in his painting. In

1618, Guercino, in Arcadian Shepherds re-expresses the theme of Poussin

on canvas using the less subtle image of a skull. In 1625 Pieter Claesz, created

Vanitas. By this time the use of the Skull as the prevalent symbol of

Memento Mori had become more or less standard.

Representations of Memento Mori appear in very early Classical

literature. As an example I quote here the words of Sophocles (circa 429 BCE) in Oedipuis the King[x]:

“Let

every man in mankind’s frailty

Consider

his last day; and let none

Presume

on his good fortune until he find

Life,

at his death, a memory without pain.”

The historian

Jean Delumeau[xi]

reports references to Memento Mori in a fourteenth-century manuscript of

the Catalan poem, Dansa de la Mort:

"Toward death we hasten, / Let us sin no more, sin no more". The

Ars Moriendi, or "Art of Dying," is a body of Christian

literature developed by the Church which appeared in Europe during the early

fifteenth century, and which underwent extensive revision up until the

eighteenth century. The Ars Moriendi offered guidance for the dying and

those attending to them concerning what to expect, and specified prayers,

behaviors, and attitudes that would lead to a "good death" and

subsequent salvation. More will be discussed concerning the extremely important Ars

Moriendi and its profound influence upon Christian doctrine and belief.

Literary works

of a somewhat later period frequently included reference to Memento Mori.

For example, William Shakespeare (circa 1598) in Scene 3, Act III of King

Henry IV included a line in which Falstaff declares: "I

make as good use of it as many a man doth of a Death's-Head or a Memento Mori

". Both The Rules and Exercises of Holy Living, 1650 and The

Rules and Exercises of Holy Dying[xii],

1651 by Jerome Thomas are two additional examples of literary works adding to

the body of literature incorporating themes of Memento Mori. Hydriotaphia,

Urn Burial, or a Discourse of the Sepulchral Urns lately found in Norfolk

(1650) is a notable work by Sir Thomas Browne[xiii]

with a similar theme.

The Christian Perspective

The Christian

basis for the phrase Momenti Mori has often been considered to be from Isaiah

22:13[xiv]:

"Eat and drink, for tomorrow we die!”. It is the Author’s view that

this passage from Isaiah is more closely aligned with the expressions Carpe

Diem (“Seize the Day”) or Nunc Est Bibendum (literally “Now we

must drink”)[xv]

which were used frequently in classical antiquity, especially during the period

preceding 14th Century Christianity to signify the brevity and

fragility of life. Both phrases are attributed to the poet Horace (circa 65-8

B.C.) in his various Odes. The phrase Memento Mori developed with the

growth of Renaissance Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, and salvation

of the soul in the afterlife. For Christians, thoughts of death were associated

with the transience of earthly pleasures, luxuries, possessions, and

achievements, which are of no value in the afterlife. A

Biblical reference more closely associated with the concept of Memento Mori is

that taken from Ecclesiasticus 7:40: “in all thy works be mindful of thy last

end and thou wilt never sin.” This finds ritual expression in the Catholic

rites of Ash Wednesday when ashes are placed upon the worshipers' forehead

accompanied by the words "Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust you

shall return”[xvi].

As discussed,

the Black Death had devastated Europe in the period following 1348, and its

recurrences along with other diseases continued to claim victims. Wars such as

the Hundred Years War between England and France (1337-1453) added to the death

toll. These dire conditions coincided with an important theological shift. In

the early Middle Ages the Church was primarily concerned with humanity's

collective judgment at the end of time; by the fifteenth century however this

changed to a focus upon individual judgment immediately after death. One's

individual death and judgment thus became an urgent matter which required

guidance. The Ars Moriendi figured prominently in this change in

theological focus. During the Council of Constance (1414–1418) Jean Gerson,

chancellor of the University of Paris, brought to the council an essay entitled De

Arte Moriendi. This work became the basis for the Ars Moriendi. From

the Council of Constance the Ars Moriendi was rapidly spread by the

established networks of the Dominicans and Franciscans.

The evolution of

the Ars Moriendi is pivotal to the development of the Memento Mori.

As the Ars Moriendi was revised it became a sort of illustrated book of

morality and death with individual salvation as its central theme. An English

translation of the Ars Moriendi appeared around 1450 re-titled

The Book of the Craft of Dying. According to Comper[xvii],

“the first chapter praises the deaths of good Christians and repentant sinners

who die "gladly and wilfully" in God”. It suggests that since the

best preparation for a good death is a good life, Christians should "live

. . . that they may die safely, every hour” The Ars Moriendi

indicates that deathbed repentance can yield salvation. Also per Comper[xviii],

the second chapter confronts the dying with five temptations and their

corresponding remedies; these include:

“ (1)

temptation against faith versus reaffirmation of faith;

(2)

temptation to despair versus hope for forgiveness;

(3)

temptation to impatience versus charity and patience;

(4)

temptation to vainglory or complacency versus humility and recollection of sins;

and

(5)

temptation to avarice or attachment to family and property versus detachment.”

Chapter 2

includes ten illustrations; five of which depict demons tempting the dying man

and five others which portray angels offering their inspirations (attempts to

remedy or provide spiritual healing). As the reader will clearly recognize, the

expansive growth of artwork incorporating images of Momenti Mori which

occurred during the period from the 14th through the 18th

Centuries are clearly a result of the newly developed Christian theology. I will

mention in passing that while the concepts of the Ars Moriendi were

originated by the Catholic Church, many of these same concepts were adopted

during the reformation by Protestant Churches. Later developments in Protestant

doctrine, including the concept of Grace were not however incorporated into the

symbolism of Memento Mori which espouses good works as the key to

salvation. Thus the symbolism of the Memento Mori came to represent an

entire litany of Christian doctrine and belief associated with death and dying.

Adoption by Freemasonry

Albert Mackey[xix]

describes the use of the Memento Mori as a Masonic symbol during the late

19th Century in his Enclopedia of Freemasonry as:

“…a symbol of mortality and

death. As the means for inciting the mind to the contemplation of the most

solemn of subjects, the skull and the crossbones are used in the Chamber of

Reflection ..."

Given the

extensive Christian history of the Memento

Mori it is highly likely that its use and adoption as a Masonic symbol

significantly preceded Mackey’s description. In

order to clearly understand the unique relationship between Freemasonry and the Memento

Mori, it is important to revisit the history, themes, and Rituals of those

two Chivalric Orders which specifically require Christian beliefs and

affiliation[xx].

These would of course be the Order of Malta and the Order of the Temple. The

phrase Memento Mori is used in the Candidate’s Charge for the Degree of

Order of Malta as described by Robert Macoy in his Masonic Manual[xxi]

:

“Finally,

Sir Knights, as memento mori is deeply engraved on all sublunary

enjoyments, let us ever be found in the habiliments of righteousness, traversing

the straight path of rectitude, virtue and true holiness, so that having

discharged our duty here below, performed the pilgrimage of life, burst the

bands of mortality, passed over the Jordan of death, and safely landed on the

broad shore of eternity, there, in the presence of myriads of attending angels,

we may be greeted as brethren, and received into the extended arms of the

Blessed Immanuel, and forever made to participate in his Heavenly kingdom.”

It

is this Charge which contains the best insight into the mindset of the authors

of the Degree relative to the sentiments of good works and salvation as

symbolized by the Memento Mori, which was of course fully consistent with

prevailing Christian theology. This Charge is in fact a literary Memento Mori

in its own right, using words instead of images to convey the sentiment.

It is useful

when examining the parallels between Christian Theology and the Symbolism of

both the Order of Malta and the Order of the Temple to consider the content and

theme of the Ritual associated with each. I would like to accomplish this by

providing snippets of quotations explaining the Degrees taken from the work[xxii]

of Bros. Jay Shute and John Walton:

First, regarding the Order of Malta:

“The

pass degree of the Mediterranean Pass, or Knight of St. Paul prepares the

candidate for the Order by introducing the lesson and example of the unfearing

and faithful martyr of Christianity.”

And further, regarding the Order of the Temple:

“An Order emphasizing the lessons of self-sacrifice and reverence. It is meant to

rekindle the spirit of the medieval Knights Templar devotion and self-sacrifice

to Christianity.”

And also:

“…

emphasis is placed on the solemnity and reverence associated with the

Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension of Christ. … Beautiful lessons of the

death and ascension of our Savior are inculcated and the candidate is received

into full fellowship, in the most solemn manner.”

From

these descriptions of the Orders, the themes of fearless martyrdom, self

sacrifice, belief in the resurrection and other Christian concepts are readily

apparent. Regarding the specific use of the Memento Mori in Masonry, and

in particular within the Ritual of the Order of the Temple, I would quote Richardson’s

Monitor of Freemasonry[xxiii]

as it refers to the two most memorable (for Templar Brothers) portions of that

ritual:

“…Junior

Warden leaves the room, and the candidate removes the bandage and discovers in

addition to the Bible, bowl of water, etc. a human skull and cross-bones facing

him on the table”[xxiv]

And:

“Grand

Commander: pilgrim, the fifth libation is taken in a very solemn way. It is

emblematical of the bitter cup of death, of which we must all sooner or later

taste; and even the savior of the world was not exempted, not withstanding his

repeated prayers and supplications. It is taken of pure wine from this cup

(Exhibiting a human skull), he pours the wine into it and says, - To show you

that we here practice no imposition, I give you this pledge (drinks from the

skull); He then pours more wine into the skull and presents it to the Candidate,

telling him that the fifth libation is called the sealed obligation, as it is to

seal all his former Engagements in Masonry…”

The impact of the fifth libation upon the candidate

binding himself to the Order while contemplating his own mortality is, in my own

personal experience, profound indeed.

Thus we have the elements which make sense of the adoption by the Chivalric

Christian Orders of the Memento Mori as a reminder that to achieve

salvation one must live a life of virtue, subduing vanity, and embracing

humility and self-sacrifice. I would hasten to add that such a prescription was

commonly accepted among Christian Mystics[xxv],

including Albertus Magnus (1200–1280); Julian

of Norwich (1342-1416);

Joan of Arc (1412-1431); Martin Luther (1483–1546);

Paracelsus (1493-1541); Giordano Bruno (1548-1600); Jacob Boehm (1575-1624);

Thomas Vaughan (1621-1666) aka Eugenius Philalethes; William Blake (1757-1827);

and William Wordsworth (1770-1850), to name just a few.

Conclusion

What does the Memento

Mori and its symbolism tell us about the philosophy of Freemasonry

concerning death and dying ? First,

let me state that many people, including some Masons, make the erroneous

assumption that the third degree of Freemasonry somehow represents death;

actually it represents rebirth. This rebirth is spiritual, moral, and

intellectual. The story of the death and raising of Hiram is not a Masonic

Passion Play, nor does it allude to the resurrection of Christ. In keeping with

this the symbol of the Memento Mori does not offer a theological

explanation of what occurs after our death. It does tell us that life is

temporal and that we should live it with that in mind, and that we should live

our lives in a moral fashion. Since the Order of Malta and the Order of the

Temple are in every respect Christian Orders, it may be logically extended that

Masons of these Orders will have beliefs on death and dying consistent with

Christian tradition.

There is no

doubt that man, possessing the faculty of self-awareness struggles endlessly

with the ontological confrontation of death. As Masons (regardless of our

religious tradition), it is good to periodically reflect upon our lives and our

beliefs as we each seek come to terms with our own mortality. Memento Mori.

![]()

Subscribe News by Email

Subscribe News by Email

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()